GARETH PEIRCE: ‘It is not the first time in history that the Court of Appeal has been an impediment to cases being reopened. There have been battles in the past on the psychology of the Court of Appeal. They have been essential to wage. The Court of Appeal was shamed into admitting that year after year, decade after decade, they kept innocent people in prison.’

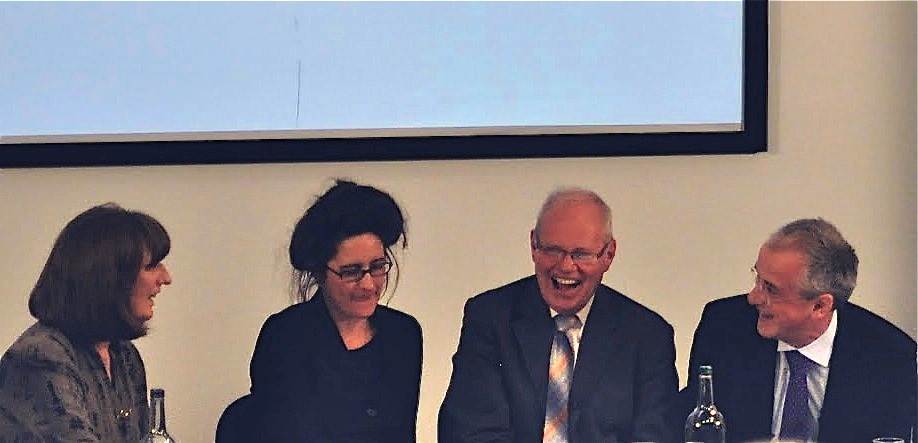

Gareth Peirce, speaking at the launch of Wrongly accused: Who is responsible for investigating miscarriages of justice? at the College of Law last week, the fourth publication in the JusticeGap series (published by the Solicitors Journal).

Why should we care about miscarriages of justice? was the opening question asked by chair Francis FitzGibbon QC, of Doughty Street Chambers. The panel comprised human rights lawyer Gareth Peirce; the pioneering journalist David Jessel; veteran defence lawyer Campbell Malone; Emily Bolton, project manager with the fledgling Centre for Criminal Appeals; and Alastair MacGregor QC, deputy chair of the Criminal Cases Review Commission.

‘It is very clear why we should care,’ replied Alastair MacGregor of the Criminal Cases Review Commission. ‘It is hard to think of a more obvious abuse of the power of the state. It is only through campaigning and challenging miscarriages of justice that we keep the system safe.’

‘You ask why we should care about miscarriages of justice, the answer is most people don’t,’ replied David Jessel, who campaigned for the creation of the CCRC through programmes like Rough Justice and Trial & Error. There was a time when the successful overturning of a miscarriage case in the Court of Appeal would be front page of the Guardian, the journalist said. ‘There is a chance a good case won’t make it anywhere in the Guardian, not even Guardian online. The issue has just sunk away.’ Jessel quoted Channel 4 chief exec Michael Jackson, who axed Trial & Error saying that the show was ‘a bit 1980s’. ‘These things come and go. There is no longer the civic empathy,’ said Jessel.

‘Our system of criminal justice is not perfect. Despite all its safeguards and the strivings of the vast majority of those of us who are involved in its conduct, a risk of miscarriages remains. Even in the current state of the public finances, we must continue to recognise and to confront that risk… [We] can all agree that further improvements are possible but what should they be? This is thus a question that is ripe for consideration in the Justice Gap series. The result is an excellent and thought-provoking collection of essays by distinguished authors from across the spectrum of involvement and interest.’

From Mr Justice Sweeney’s introduction to Wrongly accused

- You can download a copy of Wrongly accused HERE.

Black box data

Emily Bolton, who set up in the Innocence Project New Orleans, pointed to the ‘the devastation felt by the wrongly convicted’. ‘That is why we should care. But from the perspective of lawyers, it gives us the opportunity to audit the criminal justice system. If an airplane crashes we all rush to the black box and see what went wrong. Wrongful conviction cases are black box data. We need to go into that box to find out what went wrong and prevent it occurring again through legislative reform or policy reform.’

Campbell Malone is chairman of the Criminal Appeal Lawyers Association – their conference later this month is called: ‘Miscarriages of justice who cares?’. CALA was set up ‘out of despair at the way the Court of Appeal was going’. ‘I can speak about cases where miscarriages of justice not only destroyed lives but ended lives prematurely.’ He spoke of ‘well-known cases where men have served sentences and had been released on appeal to great acclaim – and within a very short period of time died’. For example, Stefan Kiszko, who served 16 years and died at 44 just 18 months after becoming a free man.

According to Malone, the ‘turning point’ was under New Labour and the ‘perceived need to rebalance things in favour of the victim and against the alleged perpetrator’. As the then prime minister, Tony Blair once infamously put it: ‘It is perhaps the biggest miscarriage of justice in today’s system when the guilty walks away unpunished.’ (In a single sentence, Helena Kennedy QC noted, the former PM ‘sought to overturn centuries of legal principle… whereby the conviction of an innocent man is deemed the greatest miscarriage of justice’.)

Ever-present danger

Gareth Peirce warned against looking at miscarriages as those cases where people had been locked away for years and there was ‘some identifiable process such as the CCRC trying to achieve an appeal’.

‘You have to understand this is an ever present danger in every case every day.’ She pointed out that the Birmingham 6’s original lawyers ‘who saw them first when they were beaten up, got their legal aid forms signed but failed to note their injuries’.

‘Lawyers are at the heart of many cases of the wrongly accused and wrongly convicted: wrong, shoddy, lazy representation. It is a recurrent theme. It should haunt us.’

Gareth Peirce

Peirce (who represented Judith Ward, Birmingham Six and Guildford Four) also talked of pressures ‘not just of the traditional kind’.

‘If people are facing extreme sentences, the innocent might plead guilty to escape what they see looming; or the guilty might plead not guilty to evade it. There are those pressures that distort the whole mechanism of so-called justice right from the beginning. One has to think of all of those interfering, contaminating factors that cause a death of justice.’

Gareth Peirce

Frances FitzGibbon asked if the situation was ‘likely to get worse’ through ‘the degradation of legal aid’. David Jessel asked Campbell Malone ‘how many pages of unused material – where all the gold is – is someone like you paid to read?’

‘You are not paid at all,’ Malone replied. ‘I know of cases where solicitors will proudly say that they haven’t even read the used material without any degree of shame.’ Malone described himself as ‘profoundly miserable’ about the prospect of the quality of investigative work improving as a result of the legal aid reforms.

‘Many, probably most’ wrongly convicted cases have not been reopened because there was funding, Peirce pointed out. ‘It is wrong to think that. They are probably reopened through a combination of circumstances. The determination in prison of somebody that their voice be heard, or their families, a campaign or a dedicated lawyer. That happens in spite of funding.’

Real possibility

An ‘abiding theme’ of the Wrongly Accused collection was criticism of the way that the CCRC works, said Francis FitzGibbon. Emily Bolton offered the perspective of somebody who has practised in the United States. ‘Lawyers would queue up around the block to have an organisation like the CCRC, simply to have an independent body with the power to go about and gather documents. That is gold dust in undoing wrongful convictions. Whatever the criticisms are, it is so important that that baby doesn’t get thrown out with the bathwater.’

Alastair MacGregor reminded the audience ‘we have something quite extraordinary in the CCRC – a state-funded independent organisation whose job it is to investigate alleged miscarriages’. ‘It has enormous powers obtaining documents from any public body: no matter how confidential, secret they may be. We can and do get to see the police, CPS, court files, security services documents and police intelligence.’

‘On top of that we have remarkable powers to send a case back to the Court of Appeal, and to make the Court of Appeal listen. It is absolutely vital that we remember just what we can do and understand the dangers of destabilising that. This is not a political climate in which the government is keen to throw money away or assist the victims of miscarriages justice.’

Alastair MacGregor

Francis FitzGibbon also asked McGregor whether the commission was ‘inhibited by statute’. The Innocence Network UK, an umbrella group for the university-based Innocence Projects set up by law students to investigate miscarriage cases, recently called for an overhaul of the CCRC. It argues that the CCRC is hamstrung by the statutory straitjacket of the Criminal Appeal Act 1995 requiring only cases with the ‘real possibility’ of the conviction being overturned to be referred to the court of appeal.

MacGregor replied that their critics ‘need to answer the question: what is the point of sending back to the Court of Appeal a conviction where there is no real possibility that the Court of Appeal is going to overturn it?’

‘It may be that we are sometimes overcautious but it is difficult to know. We do not think we are. Where is the evidence that we are?’ he asked.

David Jessel was a CCRC commissioner. Of his time there, he said: ‘I have never seen any cowardice or caution. They are some of the most committed, buccaneering types I know.’

‘What miscarriage of justice campaigners were all about was banging on the doors of the Court of Appeal and sending cases back until they got it bloody right – whether it was Carl Bridgewater or the Birmingham 6. Sending it back until the penny dropped.’ David Jessel

But the CCRC was ‘constrained by real possibility’. If the CCRC’s powers of investigation were ‘the good fairy at the christening of the CCRC, then real possibility was the bad fairy’, he said.

‘The Court of Appeal has always been like that. It has always behaved when there is an appeal like headmaster expelling a pupil: “I do not wish to see you in my school again…”.’

Gareth Peirce

She referred to the case of David Cooper and Michael MacMahon ‘which went back five and on the fifth time the commission – I give you credit there – sent it back’.

Alastair MacGregor said that if the CCRC was to start sending cases back to the Court of Appeal which they thought were a complete waste of time ‘you can bet your bottom dollar the Court of Appeal would be very quickly pushing for a change in legislation’. ‘They have reason to be concerned about being deluged with what they might see as unworthy appeals. My own view is that we should be able in exceptional circumstances – if it is in the interests of justice – to refer a case even though we do not think there is a “real possibility” to make the Court of Appeal justify itself even if we do not really think it is going to have an effect.’ However MacGregor said that such an approach ‘builds in scope for conflict between us and the Court of Appeal.’ ‘The number of times it is right for us to do so will have to be fairly limited.’

Gareth Peirce said she was ‘profoundly shocked’.

‘It is intensely disturbing. It is if you are budgeting the number of innocent people who can get their cases before the Court of Appeal. If this room was full of people who were all innocent in prison and they heard this, I think they would be utterly horrified at the basis on which you are making decisions. You are making decisions collectively as to a kind of quota system in which you try and think ahead of what the Court of Appeal might do.’

Gareth Peirce

The lawyer argued this was ‘not the first time in history the Court of Appeal has been an impediment to cases being reopened’.

‘There have been battles in the past on the psychology of the Court and they have been essential to wage. At the end of the day it was not the Court of Appeal that won. The Court of Appeal was shamed into admitting that year after year, decade after decade, they kept innocent people in prison. The Court of Appeal was exposed to the scrutiny of the world and behaved very badly and was seen to behave badly. When it came to light that dozens of people had been imprisoned – not just for a year or so but for decades – the Court of Appeal changed and appeals began to be won in a significant way that they have not been before.’

Gareth Peirce

Peirce added that she ‘sincerely believed’ that the CCRC was ‘losing an opportunity to take on the Court of Appeal’. ‘If you think it’s approach is wrong. You should be doing something about it.’

MacGregor said he was ‘surprised you are shocked’. ‘Sometimes there are times when the cage should be shaken. And I’m suggesting that there are certain circumstances where the statue should be changed but to criticise us for not sending cases to the Court of Appeal where there is not a “real possibility” is unfair.’

Peirce countered that the CCRC was in ‘an ideal position’ to challenge the court or to take a judicial review of ‘the unlawful restriction on your powers’ and ‘if necessary’ go to the European Court of human rights’. ‘You have the data. You have the data to cause a change.’ ‘I wish we felt as powerful as you think we are,’ replied MacGregor.

Dark days again

Is the implication that the Court of Appeal ‘has gone backwards to the dark days’, asked Francis FitzGibbon? Gareth Peirce described the court as ‘pretty static’. ‘I think the pendulum has swung back completely and we are facing a Court of Appeal which I believe is as conservative as it has ever been,’ said Malone.

‘Whilst there are problems with the CCRC, it has become a soft target. The real problems are with the Court of Appeal.’

Campbell Malone

FitzGibbbon also asked panelists what they thought about ‘the distinction between ‘failures of due process’, on the one hand, and establishing a person’s ‘factual innocence on the other’. ‘Working in the US we have to establish actual innocence by clear and convincing evidence. That is a standard that makes it very hard for people to get out of prison,” said Emily Bolton. ‘The unsafe conviction concept is a much easier standard for a prisoner to meet. As a practitioner I would not want to be meeting the standard of review where I had to prove factual innocence.’

Campbell Malone said that in 40 years he had he had advised ‘many people who I have felt to be innocent; but I have only dealt with one that I have known to be innocent on the basis of clear scientific evidence’ (Stefan Kiszko). ‘I’m old-fashioned and I believe passionately you are innocent until you’re proved guilty; and you are only proved guilty when you have had a fair and proper trial. If that breaks down, it is established you are innocent as far as I’m concerned.’

New suspect community

Campbell Malone went on to say that the ‘classic ingredients’ of a miscarriage were ‘defective investigation; inadequate and incompetent defence; and an unwilling Court of Appeal to put matters right. Most miscarriages of justice have those ingredients. ‘

‘The other ingredient is a fixed idea by the police and prosecutors of a pre-existing thesis,’ said Peirce. ‘It could relate to an individual or an entire suspect community.’ ‘We have repeatedly in this country had suspect communities whether they be the miners during the miners’ strike or the “stop and search” of entire communities, or the Irish people or now the Muslim community. The nature of suspicion of the Muslim community in this country is unnerving in a different way. It does not depend on forensic evidence. It does not depend upon signed confessions.‘

The suspicion depended in part on how you classified ‘interest and dissemination of material that one would think would be protected by freedom of speech’. It was storing up for the future ‘the kinds of miscarriages of justice that are never going to be undone’. ‘They are incapable of being undone because they are not based upon tangible evidence of the classic kind that you can prove is wrong. That is part of the way that the state is making an accusation just like in America in the McCarthyite era.’