Last week a unanimous verdict of not guilty was delivered in the trial of Alfie Meadows and Zak King, writes Nadine El-Enany.

- Nadine El-Enany is Lecturer in Law at Birkbeck, University of London and is on the steering committee of Defend the Right to Protest.

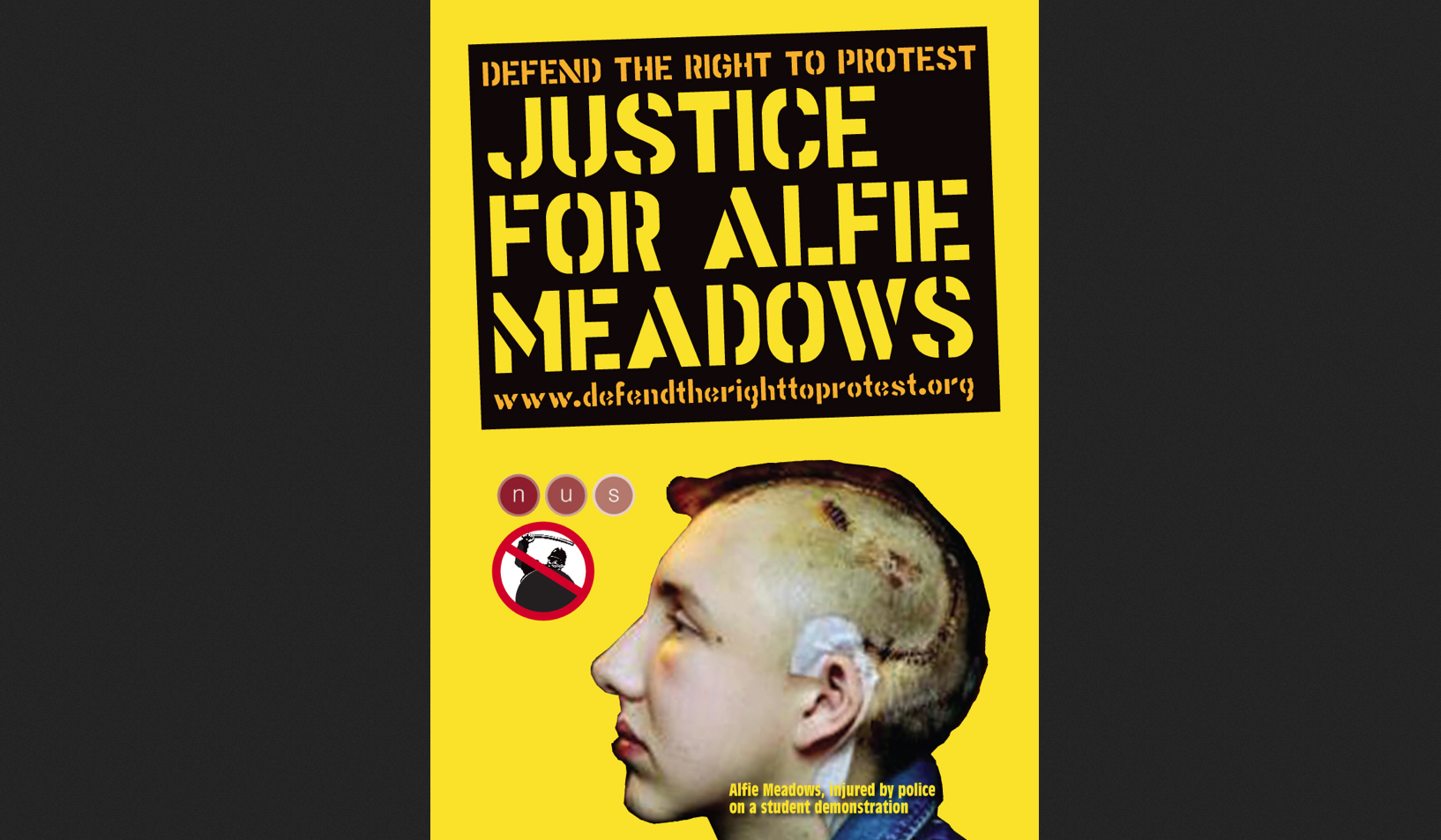

Alfie and Zak were charged with violent disorder after participating in the student demonstration of 9 December 2010 against the tripling of tuition fees, and cuts to higher education funding and education maintenance allowance. Both had waited for more than two years, and endured two trials – the first resulted in a hung jury – to clear their names. This is, however, only the first step to justice for Alfie.

Long time coming

As yet, no officer has been brought to account for the life-threatening head injury he suffered at the same protest after being hit with a police truncheon. For the time being, we can celebrate what is a long-awaited and crucial victory for the right to protest.

These verdicts mean that of the 19 students who fought charges of violent disorder following the student protests, 18 have been acquitted. The offence of violent disorder was introduced by the Public Order Act 1986 as a response to political protest and industrial activism which the then Thatcher government sought to quell by criminalising it with a flexible, serious, offence. Violent disorder is the second most serious public order offence and carries a prison sentence of up to five years. By prosecuting protesters in this way, the CPS and the police are creating a situation whereby individuals will be deterred from protesting for fear of being criminalised.

What have we learned from the trials? That public order policing today is in a state of deep crisis, from the death of Ian Tomlinson at the G20 protest in 2009 and the serious head injury sustained by Alfie to the numerous protesters criminalised for their role in public protest.

There is something fundamentally rotten at the heart of public order policing.

All this has occurred on the watch of Silver Commander Mick Johnson, whose CV boasts of a series of major public order events he has overseen at various levels, including the Poll Tax riots in 1990, the May Day protest of 2001 during which protesters were kettled in Oxford Circus, demos outside the Israeli embassy and the G20 protest.

Johnson presided over the police operation on the 9 December 2010 student demo where protesters were charged with horses, beaten with batons and kettled in below-freezing temperatures for hours, in Parliament Square and on Westminster Bridge. In the course of the trial it was also revealed that the police had considered the use of rubber bullets against the student protesters.

Bewilderingly, Johnson claimed not to have heard of Jody Macintyre, who was pulled out of his wheelchair by a police officer at a student demo – force described as ‘excessive’ by the IPCC – and thought that nothing went ‘wrong’ at the G20 protests, during which Ian Tomlinson died after being hit with a police truncheon.

Last resort

While Johnson oversaw the police operation from a control room, his right-hand man, Officer Wood, was in charge of the ground operation. Despite Wood’s claim that batons should only be used as ‘an absolute last resort’, when shown footage of officers using batons against protesters with their palms raised and heads turned away, Wood claimed he was behind his officers ‘100%’ who in his words, had shown ‘superb restraint’. ‘Apart from giving the protesters a bunch of flowers,’ he said, ‘I don’t know what else they could have done’.

When challenged by Alfie’s defence barrister, Carol Hawley of Tooks Chambers, on whether batons had been used against protesters as a last resort, Wood’s reply was that ‘the absolute last resort would be if I got a machine gun out and started shooting’.

Despite the court having been shown images of terrified protesters being hit about the head with police batons by officers, including a police medic, Johnson described the use of batons at the demonstration as ‘unremarkable’. Officers confirmed that in training they are instructed not to strike at the head. It would seem however that the code of conduct on baton use is merely ornamental.

On being confronted with footage of an officer striking a protester on the collarbone, Wood agreed that the officer had ‘gone for it: a full blooded blow’. He insisted, however, that ‘there must be a reason…[the officer] knows he’s on film. He knows if he gets caught he faces possible prosecution’.

However, the fact of the matter is that the CPS is unwilling to prosecute police officers. Not one has been convicted of manslaughter for a crime committed while on duty since 1986, though since then hundreds have died in police custody or after contact with the police.

More than 1,000 people have died in police custody since the 1960s (more than 300 between 1999 and 2010) and in only one case, in 1969, has a police officer been convicted.

That the police are treated as above the law gives them the green light to act with impunity. This trial has demonstrated that they are a heavily armed force who have behaved savagely towards unarmed civilians and then had the gall to haul them through the courts. The police’s record at public order events is in tatters. The hope is that these not guilty verdicts will send a signal, loud and clear, that the police must be held accountable for their actions.