APPALLING VISTAS: In 1980, West Midlands Police successfully appealed against a High Court ruling that civil action for assault brought by the men convicted of the 1974 Birmingham pub bombings could proceed, writes Paul May.

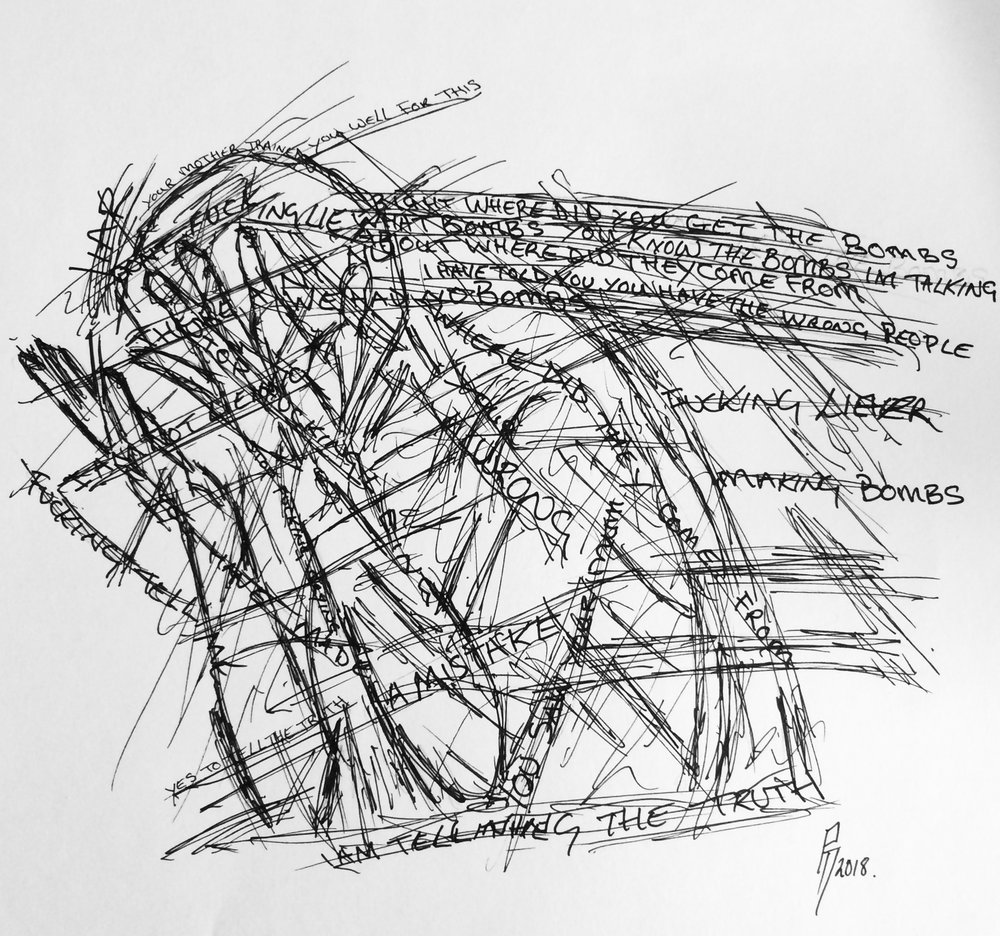

- Thanks to Isobel Williams for Appalling Vistas sketch (www.izzybody.blogspot.co.uk.)

- Appalling Vistas is a new fortnightly series offering alternative takes on law and justice

- Paul May has been involved in numerous campaigns on behalf of the victims of miscarriages from the Birmingham Six, Judith Ward, and the Bridgewater Four through to Sam Hallam , Eddie Gilfoyle and Colin Norris

In a vivid passage, Lord Denning sitting in the Court of Appeal considered the consequences if the men won their case. It would mean the police had committed perjury at the men’s trial, that confessions signed by four of them were involuntary and their convictions might be overturned. This was ‘such an appalling vista that every sensible person in the land would say: It cannot be right that these actions should go any further’. In other words, the possibility that the Birmingham Six might establish their innocence in the civil courts was too awful to contemplate and must be stopped.

At the time, Denning’s remarks received no coverage in the mainstream media outside the law reports. His contention that most people would agree with him was probably correct. The failure of the majority of the media to attempt any explanation of the causes of the Northern Ireland conflict and the seeming inexorability of paramilitary violence left most of the British public bewildered. Much of the popular press promoted the view that Irish people comprised an irrational ‘suspect community’ inherently prone to acts of violence. An extreme example arose in 1982. The Evening Standard published a cartoon which showed a bemused passer-by glancing at a cinema poster. Simian-looking ghouls brandished bombs, guns and knives under the legend ‘The Ultimate in Psychopathic Horror – THE IRISH!’. The Press Council saw nothing wrong with the proposition that an entire people was psychotically deranged. Instead, they strongly castigated Ken Livingstone’s Greater London Council for withdrawing advertising from the newspaper following the cartoon’s publication.

Under suspicion

In such a climate, it was perhaps unsurprising that manifest absurdities in the evidence against some of those accused of terrorist offences in Britain were overlooked leading to the conviction of many innocent men and women.

Time passes and new ‘suspect’ groups emerge as fresh reasons for moral panic grip the media. Currently, the attention of journalists and politicians is focussed on an unlikely target – hospital nurses. In the wake of the undoubted scandal at Stafford Hospital, media outlets almost unanimously applauded the decision of Health Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, radically to reform how student nurses are trained with the stated aim of teaching them ‘compassion’. Warnings from academics and practitioners that his plans will produce serious damage have attracted scant publicity. Senior NHS managers whose cost-cutting mania created the Stafford catastrophe will seemingly escape scot-free (and even be promoted). Doctors (who must have noticed patients were dying in improbable numbers) face no sanctions while the nursing profession must shoulder the whole blame. On 1st April 2013, several newspapers reported – without criticism – allegations by “patients’ tsar” Ann Clwyd MP. Nurses, she said, ‘just gather and chat constantly’ ignoring patients and relatives.

Images of nurses as hard-working, kindly angels have transmuted in some quarters into depictions of bone-idle malefactors hell-bent on harming patients. This process has been fuelled by cases such as suspected insulin murders at Stockport’s Stepping Hill Hospital and the 2008 conviction of former nurse Colin Norris for murder and attempted murder of five elderly Leeds hospital patients.

Surely current media opprobrium directed at nurses can’t lead to miscarriages of justice such as those prompted by the Irish community’s demonisation in the 1970s and 1980s? Another ‘appalling vista’ looms just over the horizon. In Colin Norris’s case, NHS managers, West Yorkshire Police, scientists and the courts combined to secure the conviction of an innocent staff nurse (dubbed by the media ‘The Angel of Death’) for serial murders which almost certainly never happened. Space does not allow a full description of his case (details at www.colinnorris.com) except to say that expert evidence on which the Crown relied at trial (that hypoglycaemia or low blood sugar is extremely rare among non-diabetics) was based on a medical fallacy which new authoritative research has conclusively refuted.

The Stepping Hill saga has already produced innocent victims. In July 2011, nurse Rebecca Leighton was charged with causing patients’ deaths by contaminating saline drips with insulin. The tabloid press worked itself into a prejudicial frenzy. Photographs from her Facebook account taken in social settings were published to brand Ms Leighton a narcissistic ‘party girl’. She posted – like millions of others – occasional moans about her job. Her comments were interpreted as virtual proof of her guilt. Displaying a distinct poverty of imagination, Ms Leighton was also called ‘The Angel of Death’ by some publications. In September 2011, charges against her were dropped. The Crown Prosecution Service stated vaguely that charges were ‘no longer appropriate’ adding they had believed ‘continuing investigation would provide further evidence’. This indicated a novel Micawberish approach by prosecuting authorities. First, charge a suspect then hope that some evidence turns up.

In January 2012, Greater Manchester Police arrested another nurse Victorino Chua. He seems an implausible candidate for serial murder. Friends and neighbours describe the 46 year-old Filipino as a devoted family man dedicated to his work. He has been bailed and re-arrested several times while prohibited from pursuing his profession. During almost two years investigation, police sources have issued contradictory statements casting major doubt on the inquiry itself (and indeed whether any offences have actually been committed). The media have exhibited little curiosity about the police’s investigation. In January 2013, however, an intriguing piece appeared in the Daily Star under the headline ‘Hospital murders suspect won’t be charged’. It was reported that despite 65 officers working full time on the inquiry, the case (according to a police source) ‘just isn’t ready for charges to happen. The longer the process goes on, you wonder if it’s a matter of going back to the drawing board’. Even if no charges are eventually brought, the damage has been done. The notion of killer nurses stalking the wards to inject helpless patients with insulin has been firmly established in the mind of the media and the general public.

That’s enough media-bashing for now. It should be recalled that investigations conducted by diligent print and broadcast journalists were crucial in overturning many miscarriages of justice. In October 2011, BBC Scotland broadcast an excellent film about Colin Norris’s case made by investigative journalist Mark Daly and former Rough Justice producer Louise Shorter (now of Inside Justice) albeit that the programme has yet to be aired in England and Wales.

Perhaps the final word should go to Lord Denning. In 1988, he issued a robust riposte to journalists and others looking to poke their unwelcome noses into such cases. ‘We shouldn’t have all these campaigns to get the Birmingham Six released,’ he opined, ‘if they’d been hanged’. As some cynical hack might well have commented, you really couldn’t make it up.