It is now over 20 years since Imran Khan began representing the family of murdered schoolboy Stephen Lawrence – this is the second part of a two-part interview (see HERE). He recently joined the board of the British Institute of Human Rights. He reflects on his career away from the Lawrence case, on access to justice and the importance of human rights.

- Imran Khan spoke to Oliver Lewis, who was his trainee when the initial Lawrence investigation was going on, and reflected on the case, his career and what has inspired him.

- Oliver is a higher court advocate with 20 years’ experience as a criminal defence lawyer. He was previously a partner in two legal aid firms and is now working as a freelance advocate and writer. He lives in North London and is chair of governors at a local primary school. He blogs HERE.

- You can read Oliver’s interviews with Michael Turner QC HERE and James Saunders HERE.

Imran Khan’s work these days is split between criminal work and civil actions against the police or other public authorities including a series of what he calls ‘impact cases’. ‘These are cases where there was a wider implication for society. I have been very lucky to have been involved in three or four “impact cases” since Lawrence, the most significant being that of Zahid Mubarak, the British Asian inmate at Feltham murdered by a racist cellmate, and the Victoria Climbie case, the eight year old tortured and murdered by her guardians, both of which had inquiries which led to important changes.’

The Mubarek family approached him for help after seeing him in the Lawrence case. ‘We knew what we had to do for the Mubarek family. There was a racist stuck in a cell with a young Asian lad. There was obviously something fundamentally wrong there, but we didn’t know just how wrong.’

Khan admits that he can’t take on every single case that comes his way, preferring to take on cases which have a good chance of having ‘impact’ on society. One such case is challenging the Terrorism Act, schedule 7, which permits officers to stop people at airports and detain them and question them even though they are not under arrest.

‘I first heard of schedule 7 several years ago when I represented a man arrested under the provision and discovered that suspects are obliged to co-operate – and if you don’t you are committing a criminal offence! The law doesn’t allow them to say “no comment” as you can under normal arrests. I was glad I checked, because if I had advised the man to stay silent I could have been arrested as an aider and abettor. That absence of protection against self incrimination is one of the points we are taking because you have to have a fair process and this doesn’t allow for it.’

In the year ending March 2010, there were 87,218 people stopped under the provision. Khan is acting for an individual previously arrested under terrorism legislation but who was released without charge, only later to be re-arrested under Schedule 7. Public funding was at first refused, but eventually was granted as a matter of principle. Treasury solicitors have now intervened because of the importance of the case. There will be a final hearing later this year to establish whether the legislation is compatible with the Human Rights Act.

‘If somebody stops you randomly and checks your suitcase and asks questions about you, there is this strange scenario that you are not under arrest but if you leave you will be arrested,’ Khan explains. ‘It is a bizarre, Kafkaesque situation. The Government say we need this element of protection because many people move in and out of the country and it’s a good preventative measure, given the threat of terrorism… . There’s a thin line between that and invasion of privacy.’

Khan is also taking action against the government on behalf of a young man who was allegedly tortured in Bangladesh with the complicity of the British Government. Part of the claim will be heard under the government’s secret courts measures.

The case is about ‘the way the British Government gathered intelligence linked to what was happening post 9/11’, says the lawyer. ‘This young man was over in Bangladesh and the British Government asked the Bangladesh authorities to arrest him and he was tortured for three years. We say the British Government knew what was going on and were complicit in torture.’

A kind of apartheid

A third case is a class action against the British Government on behalf of indentured Indians in Malaysia. When Malaysia became independent from the British, a constitution was drafted with British help which gave the Malays constitutional superiority over the Indians, effectively leaving many labourers and workers as slaves.

‘We say the British Government were negligent because it was the British who drafted the constitution. It has had decades’ long consequences. It’s a huge case in Malaysia and there are millions of Indians living in abject poverty, stateless, with no identity, forced into the Muslim religion.’

Khan travelled to Malaysia, but the Government blocked his entry and deported him. ‘I spent two days in the airport, it was bizarre,’ He sees a parallel to the Mau Mau case where Kenyans were tortured by British colonial forces in the 1950s. ‘The whole of Malaysia has been holding its breath to see what the outcome will be. It’s not so much about the money but they want an acknowledgement that what the British did was wrong.’

‘It’s part of the reparation movement: “You went and plundered the rest of the world, you have to acknowledge your mistakes.” Some say it’s all history and things have changed, but when you go to Malaysia you see the real effects of something that happened 50 years ago. It’s still there and the Malaysian Government continues to rely on its constitutional superiority. It’s a kind of apartheid, and the British were responsible for it.’

Return to the dark ages

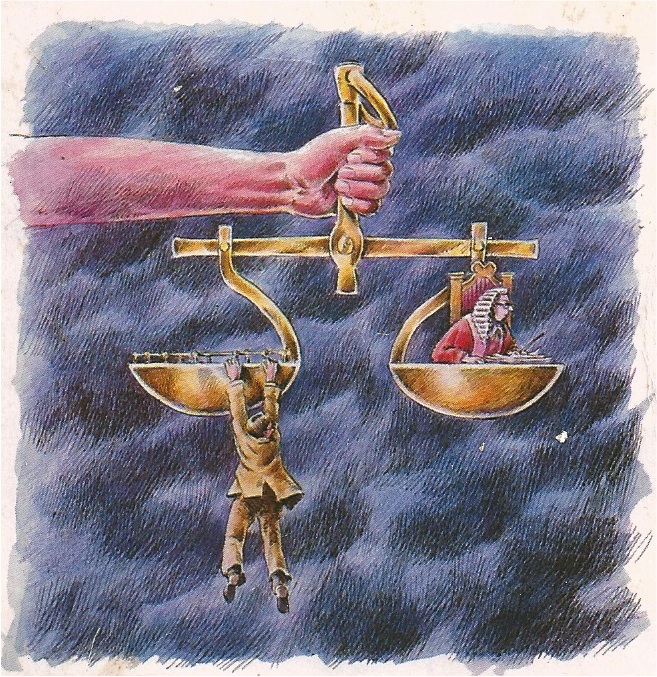

Is he worried that the current proposed changes to legal aid and structure of the profession will have an effect on people’s ability to access justice?

‘The simple truth is there’s no point in having rights if you can’t enforce them. There’s a whole swathe of society which doesn’t have access to justice. In the old days people like me and others who were seen as working within communities could do pro bono work because they could survive on legal aid; now it’s increasingly difficult. You are working twice as hard to make the same amount of money, and you just don’t have enough hours in the day. So you end up with a section in society who can’t get any access.’

What about this government’s threat to resile from Human Rights legislation?

‘In words that can be repeated? It’s atrocious! It’s the most hypocritical, outrageous action they can take. I’ve just joined the British Institute of Human Rights specifically because for me the Human Rights Act has been a symbol of how far we have come as a country and society and for this government even to be thinking about abolishing it is outrageous. They say they believe in victims’ rights and justice, but without the Human Rights Act we wouldn’t have had the Mubarek case, the Climbie case.’

‘What I am proudest about when I go abroad is there are fundamental principles that our society abide by and I think if they get rid of [the Human Rights Act], it would be the nadir, the worst thing they could possibly do. My view is that all the advances we have made in law, by and large, have their foundation in human rights or the concepts around it. Now you see these principles in judgments. Every time you go into a criminal court, fairness has a meaning much more than it used to have, a fairness based on legal principles not on a nebulous idea of gentlemen’s fairness. It is ingrained, and if we go back on that it will affect every section of our society. That is the next big challenge for lawyers, because without that framework we are back to the dark ages.’