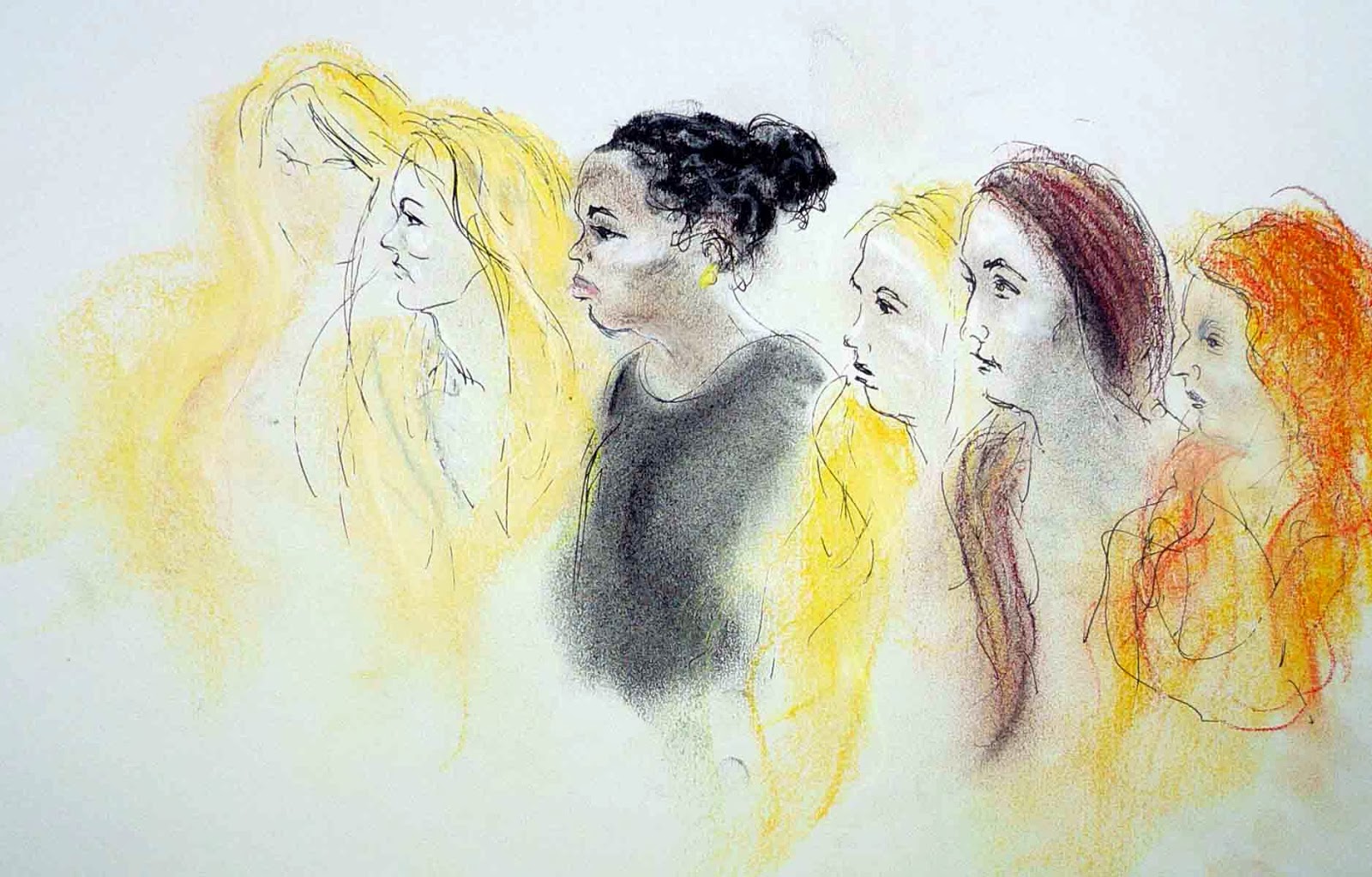

The law on joint enterprise was ‘so confusing for juries and courts alike’ that legislation was necessary to ensure justice for both victims and defendants and end the high number of cases reaching the Court of Appeal, according to a new report by MPs out yesterday. Illustration: Sehb Hundal.

Sir Alan Beith, chair of the Justice Select Committee, said that the law of joint enterprise was ‘vital’ to combat gang-related violence but was ‘so complex’ that juries might find it impossible to understand how to reach the right verdict. He urged the issue be resolved prior to a general review of the law of homicide (‘which few governments would be willing to undertake’).

The doctrine of ‘joint enterprise’ means that anyone who agrees to commit a crime with another person becomes liable for everything that person does during the offence.

- You can read an interview with Gloria Morrison of JENGbA (Joint Enterprise Not Guilty By Association) below.

- You can read about ‘joint enterprise’ on www.thejusticegap.com. Andrew Green, founder of INNOCENT writes HERE; Francis FitzGibbon QC HERE and Mark George QC HERE.

- You can read the Justice Select Committee’s report HERE.

The MPs have called upon Keir Starmer, the Director of Public Prosecutions, to produce guidance for prosecutors on joint enterprise particularly in relation to gang killings. ‘The law on joint enterprise has a role in deterring young people from becoming involved in gangs but confusion over the law and how it works can put vital witnesses in fear of coming forward, allowing the real criminals to escape justice. It is also important to ensure that young people are not unnecessarily brought into the criminal justice system when they are on the edge of gang-related activity.’

At the end of last year, five teenagers were given sentences of detention for killing 15-year-old Zac Olumegbon, stabbed to death as he arrived at school in south London in July 2010. Speaking after the case, Det Ch Insp John McFarlane said that the case ‘must act as a deterrent to other young people who think they will not be prosecuted or go to prison just because they did not deliver the fatal blow’. ‘The law on joint enterprise is clear and unforgiving – if you are with the knifeman in a murder case you too could be found guilty and sent to prison.’

The MPs took evidence from witnesses representing offenders who claim they have been wrongly convicted, those who represent people who have lost family members through gang attacks and others who ‘told us that they believed the current law on joint enterprise was leading to miscarriages of justice’.

- The Prison Reform Trust was concerned that joint enterprise might be used ‘disproportionately in cases involving children and young adults’ and could act as ‘a drag-net, bringing individuals and groups into the criminal justice system who do not necessarily need to be there’.

- Gloria Morrison, from the campaigning group JENGbA (Joint Enterprise Not Guilty By Association), argued that the ‘complexity of the law presented serious difficulties for juries’. ‘The juries often come back to the judge to say: “We don’t want to convict this person.” They are very confused. They can see who is culpable and they do not want to do it. The judge will say: “No; it’s a joint enterprise. You have to convict or acquit.”’ She reported that one case the jury received ‘a 49-page route to verdict’.

- Jean Taylor of Families Fighting for Justice, a campaign group seeking to ensure prosecutions in cases of unlawful killing, argued that ‘the lack of clarity over joint enterprise led to it being inconsistently applied’. In some cases, she told MPs people were ‘taken in just for standing by and watching’ and in other cases ‘a group or gang has been allowed to walk free…they have not been charged with joint enterprise.’

- The Committee on the Reform of Joint Enterprise (CRJE), ‘an ad hoc collection of lawyers, academics and otherwise concerned individuals and groups’, told the MPs joint enterprise and the mens rea for murder contradicted ‘three fundamental principles’ of criminal law: in the absence of a clear mental element for liability, it imputed intention or foresight; the ‘perilous slope’ involved in guiding juries on joint enterprise; and there being no connection required between the defendant and victim’s death, their guilt is ‘constructed from a wide range of precarious bases—essentially his association with the person who actually committed the murder’. This results, the CRJE concluded, with ‘the labelling of individuals who—albeit not entirely innocent—cannot properly be called “murderers”.’

Conclusions and recommendations:

- Data on the number of joint enterprise cases and appeals needed to be collated.

- The CPS and police should ‘have in mind that it is not the purpose of the law of joint enterprise to foster gang mentality or draw people into the criminal justice system inappropriately’.

- Over-charging under joint enterprise would ‘not assist the task of those trying to deter young people from becoming involved in gangs’.

- The DPP should issue guidance ‘on the proper threshold at which association potentially becomes evidence of involvement in crime’.

- The lack of clarity over the common law doctrine on joint enterprise is ‘unacceptable’ for such an important aspect of the criminal law. It should be enshrined in legislation.

- Clarification should not have to wait for a Government to embark on wider and potentially controversial changes to the law on homicide.

Interview: Gloria Morrison, from the campaigning group JENGbA (Joint Enterprise Not Guilty By Association)

Gloria Morrison’ became involved as a result of the experience of her son’s best friend. Nearly six years ago Kenneth Alexander was given a life sentence. Alexander and her son went to the same secondary school. When they left school, Gloria’s son started work for an electrical firm and Alexander joined him shortly after. Alexander is a convicted murderer as a result of his part in the April 2005 stabbing death of Michael Campbell. His case was the subject of a recent BBC Panorama (Lethal Enterprise). ‘It was Alexander’s role in ringing friends to call in reinforcements for a possible confrontation that provided the prosecution with his joint enterprise. That he knew some of his mates carried knives, even though he never did, was also a factor in his conviction.’

What does Gloria Morrison make of this new report? ‘We hope they go further. This archaic law needs further debate and a full enquiry. We want it abolished. We are encouraged that they have listened to our concerns and that those concerns have been put into a directive to the Director of Public Prosecutions. Urgency is important because it will stop further miscarriages of justice happening.’

What does she say to people who argue that these convictions send out a strong message to young people getting involved in gangs and carrying knives? ‘We are not talking about gangs. We are talking about groups of young people who are together. The idea that this is to tackle gangs is a misunderstanding. If it was successful at tackling gangs, the law would be working. This law is not working.’

Why did get involved in Alexander’s case? ‘Ken was like most people who get caught up in the “joint enterprise” situation. He took the duty solicitor and didn’t know if this man had any experience. He was part of a really cut-throat defence. Everybody was blaming everybody else. No-one owned up. From the moment Ken found out that he was convicted of murder, he like everyone else was just totally bewildered. That’s the point when I got involved. I phoned his solicitor up and I said: “how do we appeal?” He explained that you can’t appeal because you do not like the decision. Since then Ken has been moved from one prison to another. He’s a model prisoner. He doesn’t need the offending courses because he hasn’t done an offence. He is a lovely boy.’

As part of London against Injustice, Morrison put an advertisement in Inside Time calling for calling for prisoners convicted under joint enterprise and their families to attend a meeting. What was the response like? ‘Overwhelming. We booked a room for 60 and in a couple of weeks we needed a bigger room. People were standing. People realised that they were not alone. Everyone say people in prison will say that they’re innocent. The thing about ‘joint enterprise’ convictions is that it affects families so deeply. Everybody is so clear that there is a huge sense of injustice. Some 275 prisoners have contacted us. We believe it is the tip of an iceberg. The problem is bigger because this law has been used so sweepingly over the last 10 years.’

What does she think of the recent ruling in the Supreme Court where a teenager, who took part in a gunfight during which an innocent passer-by died, was guilty of murder – even though he did not fire the fatal shot (see HERE)? ‘I’m not a lawyer. I’m a campaigner. Two guys shooting at each other in the streets, they are idiots and if somebody gets killed they should be responsible. But the fact that they called it a “joint enterprise” was wrong. They were not engaged in a ‘joint enterprise’ with the same foresight and intent. They were trying to kill each other. The ruling muddies the waters even further. We have people with absolutely no involvement with a crime – none – doing a life sentence.’

‘I have visited many families and prisoners and am struck by the simple fact that these are decent people whose lives have been destroyed by this archaic law. A law that is so out of touch with modern society, that it targets the most vulnerable and marginalized in that society. Children and adults with learning difficulties, women in abusive relationships, young men on the periphery of a spontaneous act of violence, people convicted on hearsay as their co-defendents have turned Queens evidence. And most worryingly cases where people are taking a plea of a lesser charge such as manslaughter because the police tell them they will be found guilty under joint enterprise if they don’t.’ Gloria Morrison, from a talk to the Haldane Society HERE.