ANALYSIS. John Storer writes about the growing crisis enveloping a controversial new contract to run court interpreter services.

I live and work as a criminal defence lawyer in Boston, Lincolnshire, a fairly small market town, some 125 miles north of London.

John is a partner with criminal defence firm, CDA solicitors, in Lincolnshire. He entered private practice in 1988 after 16 years in magistrates' courts in Sussex, Greater Manchester and Lincolnshire.

A town that has seen dramatic changes in the last 10 years: in 2001, the population was around 35,000 and it’s now around the 45,000. The massive increase is almost exclusively down to the influx of migrant workers that have come here from other EU countries to work on the land or in the many food factories that provide most of the work here.

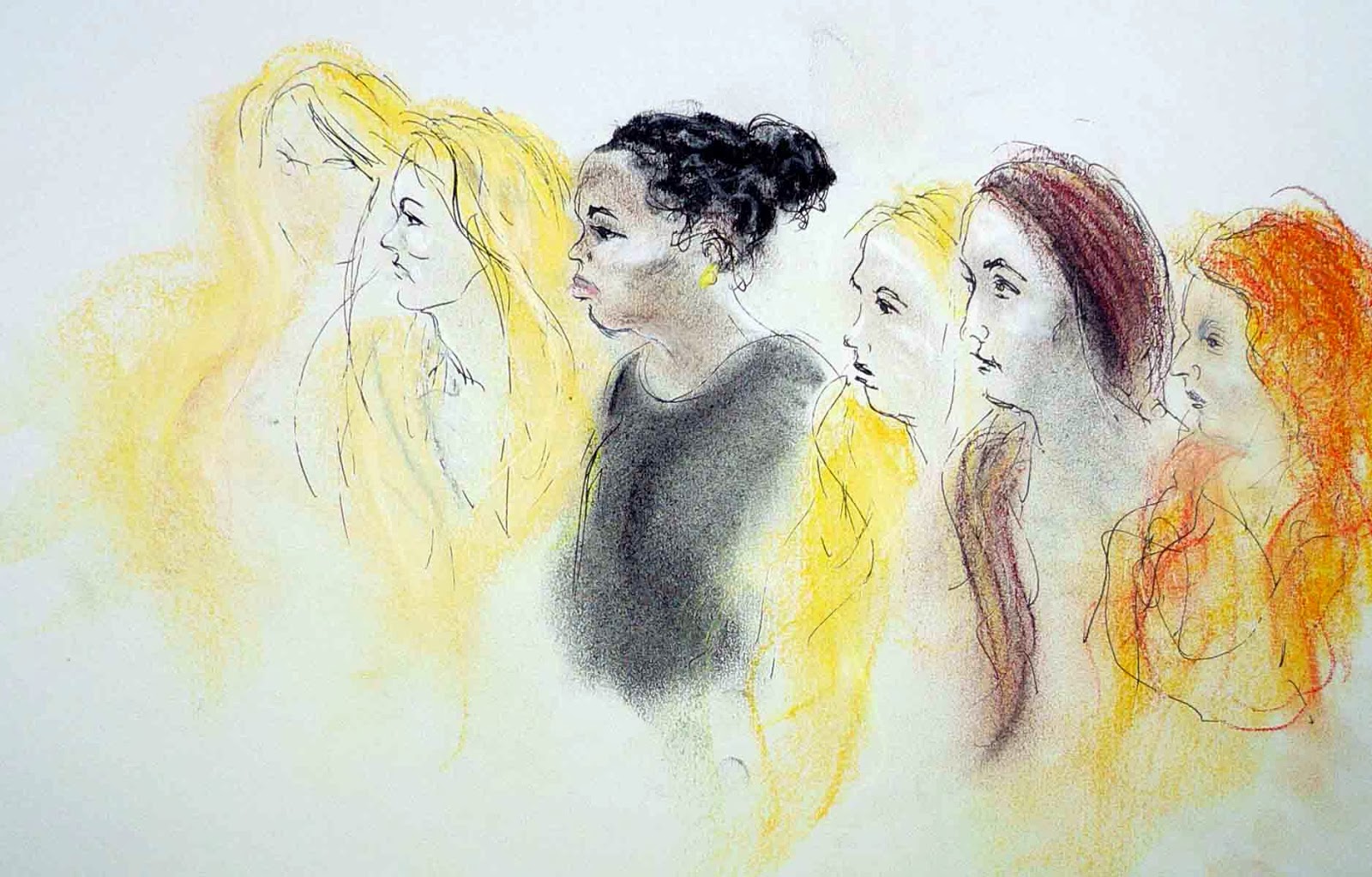

Today, some 20%-25% of our client base is non-English speaking and pretty much every court sitting has at least three interpreters. Over the years, we have got to know and, much more importantly, trust the interpreters we come across every day. They play a vital role in the proper administration of justice – not just for the defence but for police and prosecution also. Many victims of crime, and many witnesses, do not have a sufficient grasp of English to make a complaint or give a full account of what they have seen.

Interpreters are involved at the outset – from taking complaints and witness statements, through to acting as translators during interviews with suspects, and then to assisting the court in making sure the defendant or witness understands and is understood. They assist both prosecution and defence and, without them, the entire criminal justice system in our area would be in deep trouble.

So it was with some misgivings that I read that the Ministry of Justice planned to contract out interpreting requirements. My concerns increased when it was announced that the contract had been awarded and that pretty much every interpreter I knew was refusing to sign up. The warning signs were there at the outset – the contract was originally due to start in October last year but for some unannounced reason was postponed to 2012.

We had experienced problems before – Lincolnshire Police had entered into a contract several years ago with a company called CINTRA to provide interpreters at police stations. There were ‘teething problems’ at first; many of the initial interpreters sent were simply not up to the job. This caused extra public expense, because defence solicitors had to employ their own interpreters to accompany them to the police station and the cost was borne directly by the Legal Services Commission.

However, the poor ones dropped out and we were seeing interpreters of quality and, more importantly perhaps, a working knowledge of the criminal justice system. We started to have enough trust in them that the need for our own translators diminished to the point that we trusted the CINTRA interpreters entirely and began using them for defence work as well.

The figures are quite astonishing – in 2011, Lincolnshire Police made 2,200 requests for interpreters (the overwhelming majority of them being for Russian, Polish and Lithuanian speakers).

Earlier this month the Ministry of Justice announced that the contract had been given to a company called Applied Language Solutions (ALS), formed in 2003 with. It has considerable experience worldwide supplying such services. However straight after the award of the contract, Capita Group PLC (the UK’s largest provider of ‘business process outsourcing’) bought the company.

It soon became clear that many of the interpreters we knew and trusted had not signed up to work for ALS. This was because the ‘contract for services’ meant that many of them would be simply unable to work for the money being offered for their services. Previously, they had been paid for a minimum of three hours’ work with travelling and expenses. Not overly generous when one considers that would probably be their only job of the day with no guarantee of work the following day or days. The new contract is for an hour minimum with usually no travelling.

Anthony Walker, a spokesman for ALS is quoted as saying that the rates are ‘fixed and non-negotiable for everyone. This rate of pay is £22 an hour for a Tier 1 linguist and £20 per hour for a Tier 2 linguist.’

He continued: ‘These two categories being the ones that will be required to deliver the great bulk of all the work done by linguists in criminal justice settings. A very small portion of criminal justice work will fall in to the Tier 3 category at £16.’

There are few of us who can afford to work full-time with the possibility of only earning £22 in a day, let alone £16.

The contract, worth £300m over five years, is supposed to save the nation £18m a year. Quite how this adds up, when the MoJ has previously said they already spend £60m a year on interpreters and translators, is beyond me. What is clear, however, is that Capita obviously thought this was a company well worth snapping up and clearly saw huge profits.

Flight risk

Anyway, there I was at Boston Magistrates’ Court on the second or third day of the new system. I was court duty solicitor, and was told there was a young Rumanian lad in custody. He’d been charged with (and admitted when interviewed by the police) a very large shop theft. He’d never been in court before. I was told an interpreter had been booked for 9.30am.

By 11.00am, and no interpreter had arrived, I started to make enquiries. The police confirmed they had booked one, but then rang me back to tell me they had been told by ALS that ‘no one had picked up the job’. I could not even explain to my client (who had not had the benefit of legal advice whilst at the police station – his own choosing) why there was a delay.

Several phone calls later, I was told an interpreter would be with me for 1.00pm. She arrived at 1.35pm, having driven many miles from another county. I was pleased to see she was nationally-registered. The National Register of Public Service Interpreters (NRPSI) maintains a register of professional, qualified and accountable public service interpreters.

So I was sure she would know what she was doing. And she did. We dealt with the case very swiftly after her arrival. She then began to tell me some real horror stories about the quality of some of her ‘colleagues’ who had joined ALS and who held no qualifications at all.

For instance, she told me that she had heard a custody sergeant refuse a detainee bail because he was ‘a flight risk’. Anyone in the criminal justice system would know that this meant he might abscond and fail to surrender to his bail at court. However, this was translated by the ‘interpreter’ into ‘You must stay here to stop you catching a plane’

Still, I was hopeful. Here was an interpreter who knew her stuff. Perhaps there would be others like her? I have not yet found out; she is the only interpreter who has turned up for any of my cases. So far, I am personally aware of 16 cases where the interpreter has simply failed to attend. Many of these have been for defendants in custody. One was charged with murder.

ALS have confirmed that ‘some’ cases have been cancelled because the firm was unable to provide interpreters. ‘Unfortunately that has been true in some cases which is something that we are working extremely hard to resolve,’ an ALS spokesperson said. Actually, I reckon this has been true in the majority of cases in our area and it is clear that the same thing has happened in courts up and down the country.

A mess of their own making

The ALS has acknowledged that there have been circumstances where it had not been possible to fulfill a booking at short notice. It added: ‘Prior to rollout there was limited accurate management information available regarding the expected daily volumes of short notice interpreter requests.

This is a five year, £300m contract – are they seriously saying that they did not actually know what was expected to fulfill that contract?

Social media networks, such as Twitter, soon started to highlight the problems courts were facing. This was picked up by more traditional media outlets – articles have appeared in The Guardian and The Law Society Gazette. A fuss was made. The fuss got attention. So much so, in fact, that Her Majesty’s Courts & Tribunal Service issued a press release last week saying it will ‘revert to the previous arrangements for all bookings due within 24 hours at the magistrates’ courts … for urgent bookings required for bail applications, deports and fast track applications in the first tier tribunal immigration and asylum and urgent bookings in the asylum support tribunal.’

Not surprisingly, the vast majority of registered interpreters see no reason to help the MoJ out of a mess wholly of its own making and are not cooperating with this relaxation of the contract.

Things will only improve when ALS increase the rates of pay it is offering, thus tempting qualified, highly-skilled, interpreters to sign up with them. However, their new masters at Capita are unlikely to be happy with the profits from the contract being reduced – probably substantially reduced.

In the meantime, public money and court time is being wasted by delayed or aborted hearings. One suspects there is ‘limited accurate management information available’ to determine the actual cost but it is increasing by the day.

Please be quiet

I cannot end this article without commenting on my concerns about the quality of those interpreters so far signed up with ALS. I have received anecdotal evidence (which I have no reason to doubt) of a lack of experience, knowledge of procedure, and even the language they are supposed to be translating.

The figures do tend to suggest that there will be a diminution of quality. ALS claims that they have signed 3,000 interpreters to run this contract. There are not 3,000 nationally-registered interpreters (the NRPSI website says there are ‘over 2,000’). Of those members, at least 40% – probably many more – have refused to enrol with ALS. I would be greatly surprised if even 30% of the 3,000 interpreters have the necessary qualifications and experience to work in the criminal justice system

Probably the most important thing that is said to a detainee when in custody at a police station is the caution. It’s complicated for most lay persons in English, so its careful and accurate translation is crucial to the course of justice. Every day, what is said after that caution is administered impacts on just about every trial in every criminal court.

The caution starts ‘You do not have to say anything …’ reminding the interviewee of his or her right to remain silent and not answer questions. A basic right at the heart of criminal justice – the right not to self-incriminate. The caution then goes on to say ‘… but it may harm your defence if you do not mention, when questioned, something you later rely on in court’. This reminds the detainee that remaining silent may impact upon his trial and that the court can draw a conclusion that his remaining silent was because he had no defence to offer, or that a subsequent explanation at trial may not be believed.

It is therefore extremely worrying that an interpreter of my acquaintance, one of the most experienced (and trusted) in the area, recounts an interview where ‘You do not have to say anything’ was translated by the interpreter as ‘Please be quiet’

I imagine that the knock-on effects of this contract will be occupying the Court of Appeal in the months to come.