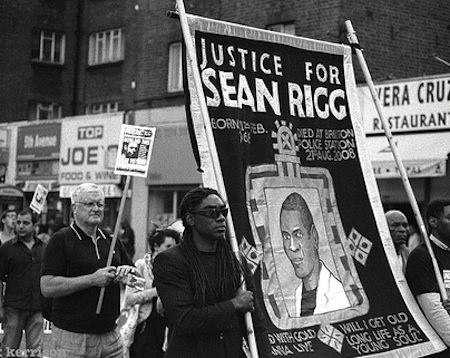

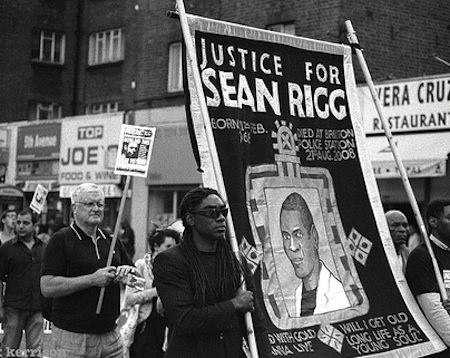

The question of who polices the police is more than rhetorical, writes Michael Etienne. It is a question posed in title of Ken Faro’s hard-hitting film documenting the death of Sean Rigg at Brixton Police Station in 2008 and his family’s campaign to bring those responsible to account.

- Michael Etienne has just been called to the Bar and hopes to focus on public law and human rights. He is a Cassel Scholar and Sir Peter Duffy Award winner of Lincoln’s Inn and will undertake an internship at the European Court of Human Rights in October. He also contributed to Campaign4Justice setup in memory of David ‘Smiley Culture’ Emmanuel, who died following a police raid on his home in March 2011. He is also a supporter of the UFFC Campaign and its call for a public inquiry.

As Mr Justice Burton stated in R v HM Coroner for West Somerset and others ex parte Middleton (a case which eventually went to the Supreme Court [2004] UKHL 10):

‘In a democracy, the defects of the workings of the state should be open to public scrutiny and, where appropriate to adverse public findings’.

In no recent case have such findings been more damning than those contained in the narrative verdict delivered by the jury at Southwark Corner’s Court following Sean’s death. It is therefore fitting that the latest showing of the film should mark the start of Garden Court Chambers’ Human Rights Film Festival tomorrow.

The release of the film, made several months beforehand, was intended to coincide with the verdict and the 4th anniversary of Sean’s death. It is attracting growing interest having been shown in a number of locations across the country. ‘We are really pleased that the public is showing such an and garden interest in the film because it highlights the flaws in the Independent Police Complaints Commission and shows that it is not independent,’ says Marcia Rigg-Samuel, one of Sean’s sisters.

Since the event is now fully booked, I’m sure no one will mind if I tell you that the film is also available online here.

Rigg was a talented musician and performer, who had enjoyed success as a professional dancer. He did so in spite of the schizophrenia that he had been managing for several years. By the time of his death however, his mental health was clearly in decline, leading to the erratic behaviour that concerned local residents and care workers, and which also attracted the attention of the police.

The jury found, he died as a result of some of the most egregious failures of the state. At its worst, they found that the use of ‘unnecessary’ and ‘unsuitable’ force ‘more than minimally contributed’ to the death. It only took officers 30 seconds to handcuff him and whilst he was struggling, he was not violent. Nevertheless, Sean was restrained in a prone position on the ground of the Weir estate, a short distance from his home, for eight minutes – including having officers putting their body-weight on top of him.

The jury (whose full verdict can be read here) took the view that:

‘Up to the point of being apprehended by the Police, the condition and behaviour of Sean Rigg was physically well but mentally unwell. The majority view [was] that both Sean’s physical and mental health deteriorated during the period of restraint [and] during the walk to the police van…he was physically unwell due to the oxygen deprivation which occurred during his restraint in a prone position.’

Despite this, he was then held in a ‘V-position’ in the footwell of the cage in the police van for 13 minutes. The journey to the police station did not take this long but Rigg was left in the van for several minutes, according to one of the officers, because he was being violent and the custody suite had to be cleared – a claim rejected by the jury. By the time he was moved from the police van, ‘he was extremely unwell’ and eventually fully unconscious. He did not make it into the police station alive.

Systematic failure

He was moved from the caged area of the police van to the caged entrance area to Brixton Police station. The CCTV footage from the CCTV camera at that entrance captures the harrowing last moments of Sean’s life. Just as they had failed to respond to Sean’s deteriorating mental health, they failed to respond to his obviously deteriorating physical condition. They initially dismissed his appearance as that of someone feigning unconsciousness. It was not until more vital minutes had passed-by that someone can be heard calling out for a defibrillator. Officers attempted to resuscitate him while an ambulance was called. It was too late.

The police were not solely to blame, by any means. Whilst the strong terms of the jury’s verdict are without recent precedent, the circumstances of Sean’s death are all too familiar to families of more than 3600 people who have died in state detention since 1990 but for whom there has not been a single successful criminal prosecution.

This is a story of systemic failure, from inadequate mental health provision or crisis management, to the CAD operators who trivialised calls for help from concerned residents and community care workers concerned by Sean’s then erratic behaviour.

Under Police Reform Act 2002, s 10, the statutory purpose of the IPCC is to ensure public confidence in the accountability of the police for their mistakes. Instead, the IPCC’s investigation is shown to be excruciating in its ineptitude but also its insensitivity. In many ways, this came as no surprise to the family, ‘that reflected our experience’, says Marcia. Even so, she says hearing some of the views expressed by the IPCC in the film left her ‘flabbergasted.’

‘It’s just unbelievable that human beings could view [their role and] what happened to Sean in such a [dispassionate] way.’

The film shows how disclosure of vital CCTV footage was resisted by the police, who even suggested that some of it did not exist. Rather than immediately attend to Sean Rigg’s body and secure the scene, when investigators arrived at the station they set about producing a press release that was so inaccurate that it subsequently had to be withdrawn. The family have always felt that the IPCC investigation lacked rigour, with investigators too ready to accept an officer’s account of events at face value. In addition, the IPCC were hamstrung by their inability to compel officers to give evidence and the standard practice of officers comparing notes even where statements were provided. If proven, the subsequent suggestion that some officers actively lied to investigators would come as little surprise.

Despite considering much the same evidence as the jury, the original IPCC investigation concluded:

‘There is no evidence to suggest that the officers who arrested Mr Rigg used excessive force. Conversely however, there is evidence to show that the officers acted reasonably and proportionately during Mr Rigg’s arrest and restraint.’

Since the jury’s verdict, the IPCC have announced that an external review of their investigation, something they have never done before. It is still not clear who will conduct that review. Nor is it clear whether they will have time for that review given that their future is currently the subject of a parliamentary inquiry. The Labour Party went one step further this week by announcing its intention to abolish it, should they win the next election. This is something that Marcia would welcome:

‘The IPCC absolutely cannot survive the way it is now. It needs reform and it needs to regain public confidence. I’ve met so many families who have been in our position since Sean died and we have no faith in the IPCC. We can’t all be lying’

Whilst the anti-establishment feel of the film may be too much for some that must not obscure the essential message of the piece. Deaths in custody are a societal problem that has grown out of a toxic mix of complacency and impunity that develops where there are no effective means of implementing safeguards or ensuring accountability.

Whilst not every one of the 3600 plus deaths will have been the result of deliberate or even negligent wrongdoing, that is not say that none of them are. As this week’s report by INQUEST, ‘Learning from deaths in custody’ highlights, until there is a system in place that commands public confidence, which not only facilitates an effective investigation but also enables recommendations for reform to be implemented, the same failings will be repeated over and over again.

The Metropolitan Police Service has also announced an independent commission into how the it responds to those with mental health problems. However, it is already facing criticism for failing to consult with families and organisations such as INQUEST before making the announcement. Marcia puts it this way:

‘INQUEST’s report is absolutely vital. My family and many others welcome it but why were INQUEST not asked to be part of the commission when they have done all of the work in this area and highlighted the flaws in the system?’

There are imperative questions that must be answered. Why do the same issues persist? A disproportionate number of deaths among those from African and Caribbean communities, typically as a result of excessively forceful methods of restraint, inadequate mental health treatment with families left feeling abandoned by a system that had already failed to protect a loved-one. Sadly, there have been false dawns over reform in this area many times before.

The year that Sean Rigg died marked a decade since the death of David ‘Rocky’ Bennett whilst a mental health patient at the Norvic Clinic, in Norwich. Again as a result of being deprived of oxygen whilst being forcibly restrained, again of African Caribbean heritage. The public inquiry into his death made 22 recommendations, which included improving mental healthcare training. Perhaps most strikingly, it further recommended that ‘under no circumstances should any patient be restrained in a prone position for a longer period than three minutes.’

None of those recommendations had or have been implemented. If this vicious cycle is to be broken, this latest opportunity to effect meaningful change must not be wasted.

To sign the public petition calling for a public inquiry into deaths in police, prison, mental health & immigration detention click here. The petition is being proposed by The United Families & Friends Campaign (UFFC), of which Sean Rigg’s case is a part.