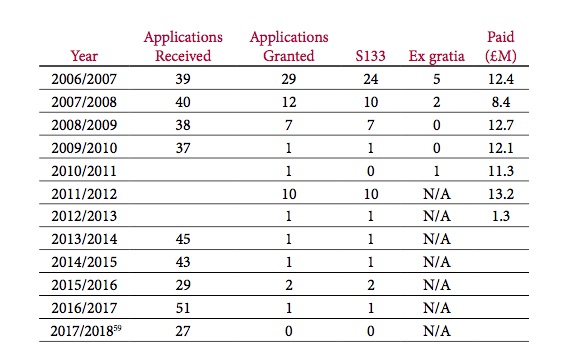

In the last five years only a handful of people have been awarded compensation as a result of having their conviction quashed and not a single person was successful last year. A new report by the law reform group JUSTICE published this week reveals how the Coalition government effectively closed off compensation for the wrongly convicted with only five successful applications since 2013/14.

Over the last 20 years there has been an average of 21 quashed convictions a year and in the last five years almost 200 victims of wrongful convictions have applied to the Ministry of Justice for compensation. However, the number of successful compensation claims has ‘plummeted’, JUSTICE reports.

In 2014/15, there were 45 applications, 20 quashed convictions and one successful compensation application; in 2015/2016, there were 17 convictions quashed and two successful applications; and in 2016/2017 there were 10 quashed convictions and one successful applicant. Last year, there were 27 applications but not a penny was paid out. By contrast in 2004/05, there were 88 applications and 48 were successful.

In its new report, JUSTICE is calling for ‘automatic compensation’ for wrongful imprisonment; better transition from prison to release; specialist psychiatric care and a residential centre; as well as an apology. North of the border, the Miscarriage of Justice Organisation (MOJO), set up by Paddy Hill of the Birmingham Six, has been calling for similar support through its ‘Say I’m Innocent’ campaign (see here).

In its new report, JUSTICE is calling for ‘automatic compensation’ for wrongful imprisonment; better transition from prison to release; specialist psychiatric care and a residential centre; as well as an apology. North of the border, the Miscarriage of Justice Organisation (MOJO), set up by Paddy Hill of the Birmingham Six, has been calling for similar support through its ‘Say I’m Innocent’ campaign (see here).

It has been 36 years since JUSTICE last published a report on the post-conviction treatment of the wrongly convicted. ‘Unfortunately, little has changed since then,’ the group said. ‘Exonerees still not do receive the support they need to return to a normal life and are not properly compensated.’ As the group makes clear, a bad situation has become worse. In 2006, the Labour government axed an ex gratia scheme to compensate the victims of miscarriages of justice. It was costing over £2 million a year to run and benefited about ten applicants a year and 20 in 2000.

That just left a statutory scheme under the Criminal Justice Act 1988, Section 133. The Coalition government’s Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 amended section 133 so that compensation payouts were restricted to those few people who could demonstrate their innocence ‘beyond reasonable doubt’. The move was described as ‘an affront to our system of law’, said Baroness Helena Kennedy in a debate as the legislation was going through the House of Lords

‘An absolute scandal’

Sam Hallam was just 17 years old when he was sent to prison for a gang-related murder he had always denied any involvement in. He spent seven years in prison before his conviction was overturned. Hallam was at the launch of the JUSTICE report earlier this week and attended this week’s Vigil for Justice (see picture). He has been refused compensation and next month (May 8) the Supreme Court will consider his case alongside the case of Victor Nealon.

Henry Blaxland QC, who acted for Hallam, called the lack of compensation available to the wrongly convicted ‘an absolute scandal’. He made the case for the reinstatement of the ex gratia scheme ‘abolished by [Home Secretary] Charles Clarke arbitrarily and without any prior announcement’. ‘It wasn’t perfect but at least it gave the Home Office the ability to intervene where the statutory criteria didn’t apply,’ the QC said. Scrapping the ex gratia scheme just left the statutory section 133 scheme which, he pointed out, was ‘only ever meant to be a safety net.’ You can read the history of this on the Justice Gap here.

Matt Foot, Sam Hallam’s solicitor, pointed out innocent people seeking to overturn a wrongful conviction faced almost impossible odds. ‘The CCRC are the only body who can refer a case back to the Court of Appeal and last year they only referred 0.77% of all cases: just 12 cases and only one murder case,’ he said. Foot called the 2014 compensation threshold ‘absolutely shocking’ which meant that the MoJ was only like to pay out if there was conclusive proof of innocence such as DNA evidence. ‘It isn’t just about compensation,’ the solicitor said. ‘It is about looking after people who have come through this experience. They are almost treated worse than a convicted prisoner. They’re left on the scrapheap with no one to look after them. They are damaged people, the experience lives with them forever.’

Neither Sam Hallam nor Victor Nealon received an apology from the Court of Appeal. In fact, the court suggested that the seventeen-year-old Hallam was the architect of his own misfortune as a result of ‘a dysfunctional lifestyle’. As has been widely reported, Nealon left prison with just a £46 discharge grant and a train ticket and would have sent his first night of freedom on the streets were it not for journalists who paid for a B&B.

If it wasn’t for Paddy, I would have been on the streets

Jonny Kamara spent 20 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit. He told the JUSTICE meeting about the circumstances in which he left prison.

I was given £46, a travel card and told to go back to Liverpool. I had to get on the train by 8pm. I had nowhere to live. I went back in my cell. They told me I was free to go but I said: “I’m not going.” I was then told if I didn’t leave the prison by six I would be arrested.

Jonny Kamara

Later that day Kamara received a phone call. ‘It was Paddy Hill from the Birmingham Six. I stayed with him for about two years. There was no aftercare. If it wasn’t for Paddy, I would have been on the streets.’

‘The biggest gap is in relation to psychological support,’ said Paul McLaughlin of MOJO which was set up by Paddy Hill. ‘… It is a disgrace. These people are in pain and desperate. They don’t know where to turn. The services that are out there are inadequate. There are people in this room still struggling years and years after being out of the prison system.’

A study by the London School of Economics in 2015 noted the ‘startling lack of statutory support’ for victims of miscarriages of justice post-release which meant that many failed even to secure social housing on release. ‘Some fail a local connection test owing to their imprisonment, while others, in a particularly Kafka-esque twist, are even deemed to have caused their own homelessness,’ it said.

There is one bespoke state-funded support service for exonorees: the Miscarriage of Justice Support Service (MJSS) funded by the Ministry of Justice and run by Citizens Advice. According to the JUSTICE report, it supports about 20 to 30 exonerees a year indefinitely with one client receiving support for about 14 years. According to JUSTICE, the MJSS ‘does not provide the extensive service that is necessary’ and efforts to engage with exonerees can be ‘ineffective’. MOJO’s Paul McLaughlin claimed two of its clients in the last six months had failed to access the service after making contact with their local citizens advice bureaux.

Eight out of 10 people helped by the MJSS have been helped have been recognised as ‘priority need’ for social housing. ‘But that has taken months and months,’ said Alison Lamb, chief executive of the Royal Courts of Justice’s CAB. ‘When people who have experienced what exonerees have experienced turn up at a local authority that authority does not recognise those circumstances as a priority need. It’s a systematic failure.’