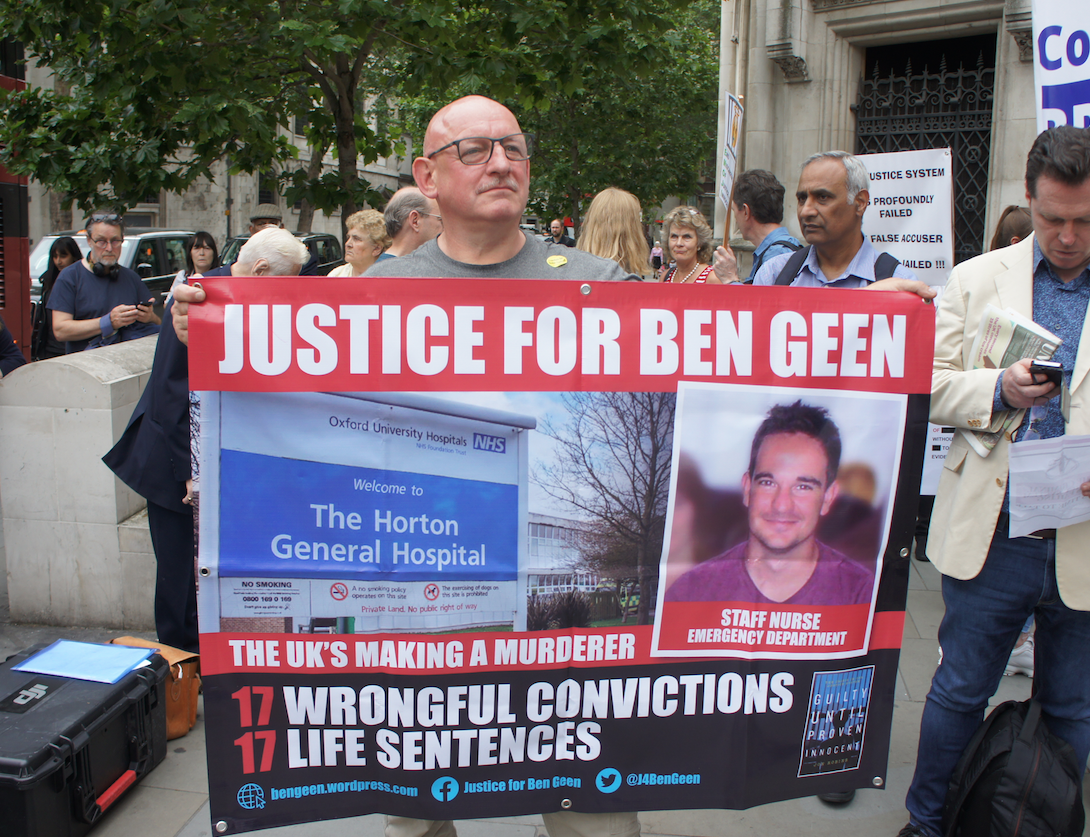

Leading statisticians have come out in support of a former nurse serving 30 years for murder in a final attempt to clear his name. The miscarriage of justice watchdog is expected to decide whether or not to refer the case of Ben Geen, currently in HMP Frankland, back to the Court of Appeal in the next few weeks. The Appeal judges have the power to overturn his conviction on two counts of murder as well as causing grievous bodily harm to 15 other patients.

Geen was portrayed in the press as ‘the nurse who killed for kicks’ and sent to prison in 2003. He was sentenced shortly after the publication of a report into the conduct of the GP Harold Shipman considered to be the UK’s most prolific serial killer. The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) had previously rejected the case but has been forced to reconsider their decision in the wake of a legal challenge.

- The Ben Geen case has featured on the Justice Gap here.

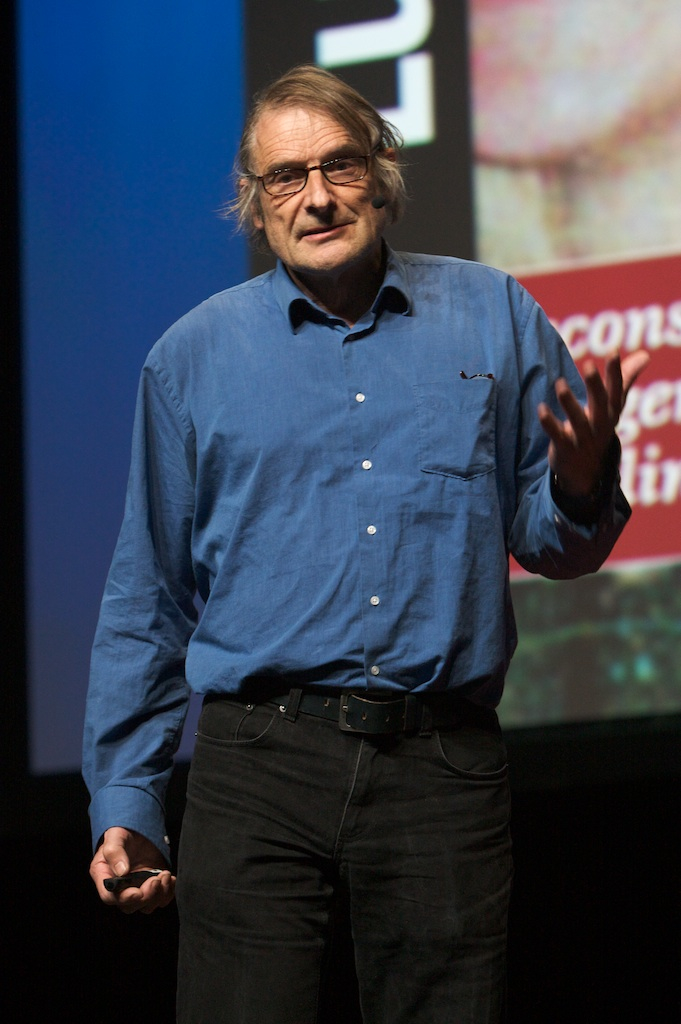

‘We have grave doubts as to the courts’ ability to get to grips with what was going on at the hospital,’ comments Professor Richard Gill, emeritus professor of mathematical statistics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

‘We have grave doubts as to the courts’ ability to get to grips with what was going on at the hospital,’ comments Professor Richard Gill, emeritus professor of mathematical statistics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

At his three-month trial, the Crown’s lawyers argued that incidents of respiratory arrest were extremely rare and, unheard of, without cause. They claimed that ‘an unusual pattern’ had emerged at the A&E at Horton General, a small hospital in Banbury in Oxfordshire when 18 patients apparently suffered unexplained respiratory arrests in a three-month period.

A previously rejected application to the miscarriage of justice watchdog – backed by five leading statisticians including Sir David Spiegelhalter, of Cambridge University and Professor Norman Fenton, of Queen Mary’s University of London as well as Richard Gill – argued that the likelihood of a cluster of such events was far from unusual.

A soon to be published new paper – co-authored by Gill, Fenton as well as Professors David Lagnado from University College London and Martin Neil from Queen Mary’s – for the first time draws on data as to admissions at Horton General over a 13 year period with the critical three months when Geen was supposed to have been on a killing spree at its centre.

Prof Richard Gill: a long time supporter of Ben Geen

Prof Gill was involved in the successful campaign to overturn the conviction of the Dutch nurse Lucia de Berk – see below. According to the academic, up to mid-2004 admissions at the hospital were getting busier and busier. ‘The number of patients being treated in emergency almost doubled from 400 a month in 1999 to about 800 by the time of Ben’s arrest in February 2004,’ he explains. ‘Then the numbers collapse – no doubt, the fall was initially due to the public’s response to Ben’s arrest but it seems almost certain that the numbers fell (and stayed low for a long period) as deliberate policy of the local health providers. And nobody has ever said why they changed their policies.’

‘The claim that the emergency room was chronically understaffed during the critical months was part of Ben’s defence. It was denied by the hospital,’ Gill continues. He points out that Geen had complained about the situation times in the three critical months. ‘He was severely reprimanded by the chief nurse for doing so. The official line was everything was going fine,’ Gill says. ‘The reality was it was getting more and more chaotic and things were going wrong, patients were waiting too long. Everybody denied that.’

The new report argues that events might have been relabelled after hospital management suspected Geen. An internal investigation was launched after a 42-year-old diabetic alcoholic arrived on a Thursday afternoon complaining of abdominal pains. Within hours he was fighting for breath, put on a life support machine and later died. It was the second time that day that a patient appeared to suffer an unexpected respiratory arrest.

Senior staff at Horton General called in doctors from nearby John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford and, over the weekend, went through case notes. Ben Geen was the only member of staff under suspicion. By the end of the weekend, the team identified 18 patients as having suffered an unexplained respiratory arrest and on each occasion Geen had been on duty. ‘They did not look for events outside his shifts,’ says Gill. ‘Many of the events they identified had not even been thought of as in any way suspicious before. Some were very mild and did not lead to admission to critical care. Many other of those patients were on their way to critical care anyway.’

The following Monday, Ben Geen was arrested. As he arrived for a night shift, he was called into a meeting. He had a syringe in his jacket pocket and discharged its contents into its lining. The prosecution alleged that the man whose death sparked the investigation tested for two of the drugs (vecuronium and midazolam) in the syringe.

According to the new paper, the classification of such collapses is far from precise at the best of times and certainly not in an understaffed environment. A diagnosis of ‘cardio-respiratory’ arrest, where the heart stops working and consequently the lungs fail, is far more common than pure ’respiratory arrest’ where the lungs stop working, and hypoglycaemic episodes, involving a fall in blood glucose level causing fainting.

The new report argues that the data over the 13 year period for the total number of arrests over the critical three month period was completely in line with what would be expected. However what was striking about the period leading up to Geen’s arrest was the unusual mix and, in particular, the high proportion of cases identified as ‘respiratory arrest’. ‘Normally, there are five times as many cardio-respiratory arrests as respiratory arrests. Now it was the other way round,’ explains Gill. ‘Why does the number of cardio-respiratory arrests fall so suddenly in those three months? Do we really believe that there were no cardio-respiratory arrests in December 2004?’

According to Gill, it was ‘pretty clear’ that there was ‘a massive re-classification on those few days after the two cases that were the trigger for Ben’s arrest’. He continues: ‘When one looks at the medical data on those 18 patients it is clear that labelling of events is very, very arbitrary. Some ‘arrests’ were so brief that they probably should not have been called an “arrest” at all.’

Prof Norman Fenton says that ‘from a purely probabilistic viewpoint, there was always a problem with the assumption that such a cluster of “incidents” happening in a short time period with the same nurse on duty each time could not have happened by chance’. He continues: ‘Even if we ignore the possibility – as suggested by the new evidence – that at least some of the incidents may have been misclassified, the probability of such a cluster happening is not especially low. When we look at the newly available admission data for the extended period, the idea that the ‘cluster’ can only have been caused by malicious intervention is even more dubious.’

Lucia de Berk: Statistics drove the case from start to end

The following is an extract from Guilty Until Proven Innocent (Biteback 2018) by Jon Robins

Lucia de Berk, a paediatric nurse, was found guilty of seven murders and three attempted murders of children in her care at Juliana Children’s Hospital in The Hague in 2003. She was reckoned to be the Netherlands’ most prolific serial killer. At least she was until she was exonerated in 2010. Now her case is recognised as one of the country’s gravest miscarriages of justice.

Lucia de Berk, a paediatric nurse, was found guilty of seven murders and three attempted murders of children in her care at Juliana Children’s Hospital in The Hague in 2003. She was reckoned to be the Netherlands’ most prolific serial killer. At least she was until she was exonerated in 2010. Now her case is recognised as one of the country’s gravest miscarriages of justice.

The court heard that more children died on her shifts than could possibly be explained away by coincidence. The odds of her having been present by chance was reckoned to be one in 342 million. The alleged murders and attempted murders were claimed to have taken place at three hospitals between 1997 and 2001. They came to light after police began investigating the death of a baby girl named Amber. Her conviction was based on two deaths, including that of Amber, which toxicology reports suggested could have been a result of poisoning.

Statistics drove the case from start to end, according to British-born statistician Richard Gill, emeritus professor of mathematical statistics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. Gill campaigned for de Berk’s conviction to be overturned. ‘Why do we know beyond reasonable doubt that Lucia is innocent? Because an independent multidisciplinary scientific team of medical specialists, toxicologists were finally allowed complete access to complete medical dossiers of key cases,’ Gill told me. ‘They discovered that the alleged incident in each of those cases was entirely natural – though in each case there was a heap of medical errors and all kinds of important information had earlier been withheld from the courts.’

Just like the de Berk case, Geen’s began with the hospital handing over the murderer to the police. Typically, murder investigations begin with ‘an evidently murdered person’ (Dr Gill’s words) and the police are called in to find the perpetrator. However, in these cases that principle has been inverted; the police go with the story as told by the medics. ‘As we know, “medical collegiality” means that that story will be very consistent,’ he said. ‘No one will break ranks and tell a different story.’

Just like the de Berk case, Geen’s began with the hospital handing over the murderer to the police. Typically, murder investigations begin with ‘an evidently murdered person’ (Dr Gill’s words) and the police are called in to find the perpetrator. However, in these cases that principle has been inverted; the police go with the story as told by the medics. ‘As we know, “medical collegiality” means that that story will be very consistent,’ he said. ‘No one will break ranks and tell a different story.’

Prof Gill argued that the fact of Geen’s presence came to be what defined an incident as an ‘incident’. Again, that is what happened in the de Berk case. The two cases highlight the difference between the British adversarial legal system and the Continental inquisitorial system. In the Netherlands, the court can appoint a scientist to lead an investigation, which means that the judge and jury do not have to depend on the expert witnesses called by the prosecution and defence.

In Prof Gill’s view, Ben Geen was convicted simply because the prosecution had the more persuasive experts. ‘Unfortunately, Ben will never get a fair trial until medical experts start speaking out on his behalf. I am afraid that their ranks are closed,’ he said. ‘Lucia got a fair retrial because there was a medical whistleblower, well placed in society and with inside knowledge who fought for seven years.’