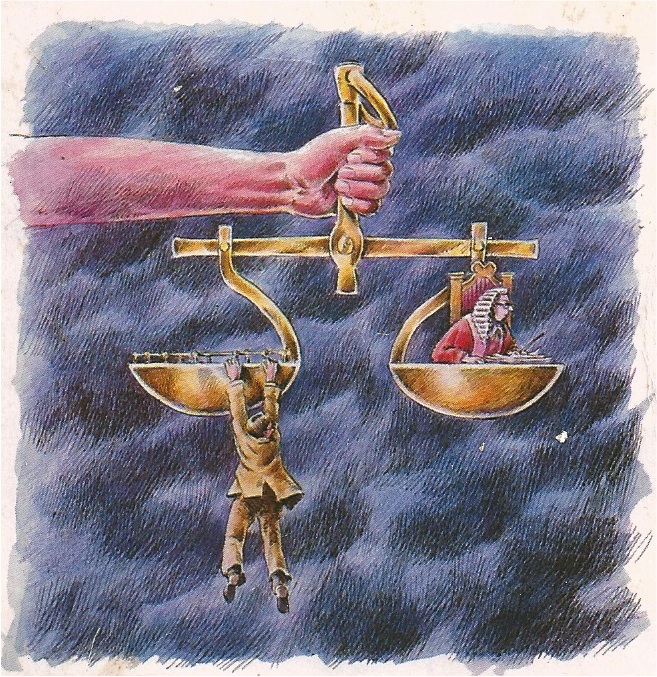

Whitehall mandarins unlawfully interfered with the independent miscarriages of justice watchdog and threatened its directors with ‘removal’, lawyers have claimed.

- A version of this article appeared in The Times this morning. It was incorrectly attributed to Jonathan Ames. It was written by Jon Robins and Jonathan Ames. All interviews were done by Jon Robins.

Correction printed July 30

The Justice Gap has seen the minutes of one of the regular meetings between civil servants and the commissioners in February 2018 when the Ministry of Justice’s deputy director, Alison Wedge, appeared to insist that the watchdog accepted changes to terms of employment for staff and to the structure of its board.

Wedge warned the commission, set up by statute in the wake of the Guildford Four and Birmingham Six debacles, that it would be ‘in conflict’ with government policy if it did not accept fundamental changes laid out in a ministerial review.

The minutes, obtained under freedom of information legislation, showed that Wedge told the commission that David Gauke, secretary of state for justice ‘recommends the appointment of commissioners to HMQ [the Queen] and that similarly he could recommend removal. However, [she] hoped that there would be no need for such a situation to arise’.

Glyn Maddocks, a lawyer and special adviser to the all-party parliamentary group on miscarriages of justice, which was launched two years ago, said that it was ‘entirely inappropriate for the MoJ to be bullying the CCRC’ in the way that the revelations suggest.

Concerns over the performance of the CCRC have mounted since it referred just a dozen cases to the Court of Appeal in 2017, only 19 cases in 2018 and just 13 last year. Maddocks argued that the squeeze on funding threatens the commission’s independence.

Earlier this week, the all-party parliamentary group launched a Westminster commission chaired by Baroness Stern and Lord Garnier, QC, a former Conservative solicitor-general, to look at the commission’s role.

The watchdog was created by the Criminal Appeal Act 1995 and began work two years later. The legislation stipulates its independence, saying: ‘The commission shall not be regarded as the servant or agent of the Crown.’

When the watchdog was launched, its budget was £7.5m and it dealt with 800 cases a year. It received just £5.45m last year with applications running at an average of 1,500 a year which means that for every £10 it had then it has £4 now.

‘We need to get to the bottom of how the funding crisis is impacting on the CCRC,’ said Maddocks. ‘To be truly independent the watchdog must be properly funded.’

‘It is also alarming that the CCRC has effectively allowed itself to be comprised. The power of the CCRC resides in the commissioners’ ability to refer these cases back to the Court of Appeal.’

Ten years ago nearly all the watchdog’s 11 commissioners were on full-time contracts with salaries and pension schemes.

Now all but one are employed on a minimum one-day-a-week contracts and paid on a £358 daily rate, and some legal experts are concerned the watchdog is not independent because commissioners no longer have tenure.

Criticism has also fallen on Richard Foster, who until last November was the commission’s chairman. Foster was a career civil servant and former chief executive of the Crown Prosecution Service.

His prosecution background created increasing cause for concern, former commissioner David Jessel, told The JG.

Mr Jessel said the approach of the original commission chairman, Sir Frederick Crawford to the government was ‘give us the money and leave us alone’.

However, the appointment of Mr Foster, ‘led to a closer relationship with the ministry, who saw the CCRC as a somewhat maverick organisation in terms of its governance’.

Mr Jessel added: ‘There were eventually bitter divisions between Foster and the Commissioners, but the Whitehall view prevailed. The influence of the commissioners – many of them distinguished and independent experts with a concern for miscarriages of justice, who supervised and guided the case workers, was drastically diminished.

‘The CCRC, and its dedicated staff, have lost some of the sense of mission which full-time Commissioners brought to the organisation’s founding vision. The paltry number of successful investigations is the result – although, laughably, the MoJ takes it as proof that the criminal justice system is working well.’

The former chief prosecutor Nazir Afzal applied for the job as CCRC chair but was not successful. He reckons that commissioners have been feeling increasingly marginalised. ‘The impact of funding can’t be exaggerated. It’s having a conscious or unconscious impact on decision making,’ he told the Justice Gap. ‘Staff clearly know that there’s a shortage of judges and judicial time added to an unnecessary requirement for a very high threshold for referral which means that fewer cases are referred. To pretend otherwise is a dereliction of duty.’

Details of the meeting between the commission and the MoJ in 2018 came to light in the High Court when a decision by the commission to reject the case of a convicted armed robber was challenged on the basis that the group is not sufficiently free of control from the Ministry of Justice.

Dean Kingham, of Swain & Co, a specialist public law and prison law solicitors’ firm, said: ‘The independence of the CCRC goes to the heart of the integrity of the justice system. Politicians need to respect that and the CCRC needs to stand up for itself.’

The Ministry of Justice declined to comment on the allegations.