Twenty years of legal aid cuts had left key parts of the justice system ‘hollowed out’ with lawyers deserting publicly-funded work as a result of fixed fees and low pay. The House of Commons’ justice committee reported that many criminal defence firms were not able to recruit or retain lawyers with ‘a significant number’ of lawyers leaving to join the Crown Prosecution Service. It was reported that 12% of defence firms gave up legal aid during the course of one year alone (2019).

‘Without significant reform there is a real chance that there will be a shortage of qualified criminal legal aid lawyers to fulfil the crucial role of defending suspects and defendants,’ the MPs said. ‘This risks a shift in the balance between prosecution and defence that could compromise the fairness of the criminal justice system.’

The MPs also looked at the civil system and the impact of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO) cuts reporting that providers were ‘facing major sustainability challenges’. ‘The rates of pay make recruitment and retention difficult with the result that in many areas there are advice deserts,’ the MPs said. The Legal Aid Agency was accused of having a ‘culture of refusal’ and MPs called upon the agency to be ‘empowered to place more trust in providers’. Full report on the impact of the civil cuts tomorrow.

In 2018, the justice committee found ‘compelling evidence’ of the ‘fragility’ of the criminal defence sector and said the risk posed to the right to a fair trial under the European Convention on Human Rights, article six, could ‘no longer be ignored’. The MPs said: ‘This inquiry has led us to the same conclusion on the fragility of criminal defence firms and the Criminal Bar. The situation in 2021 is worse than in 2018, especially due to the impact of Covid-19 on legal aid expenditure.’

The MPs quoted Sir Tom Winsor, chief inspector of constabulary, fire and rescue services, saying in January this year that before the pandemic, the criminal justice system was in ‘a severely distressed condition. Criminal defence resources were weak; legal aid rates are at chronically low levels. There were very severe delays already, decaying buildings, a crumbling infrastructure, understaffing and inadequate resourcing in all sorts of respects, and the pandemic has made things worse.’

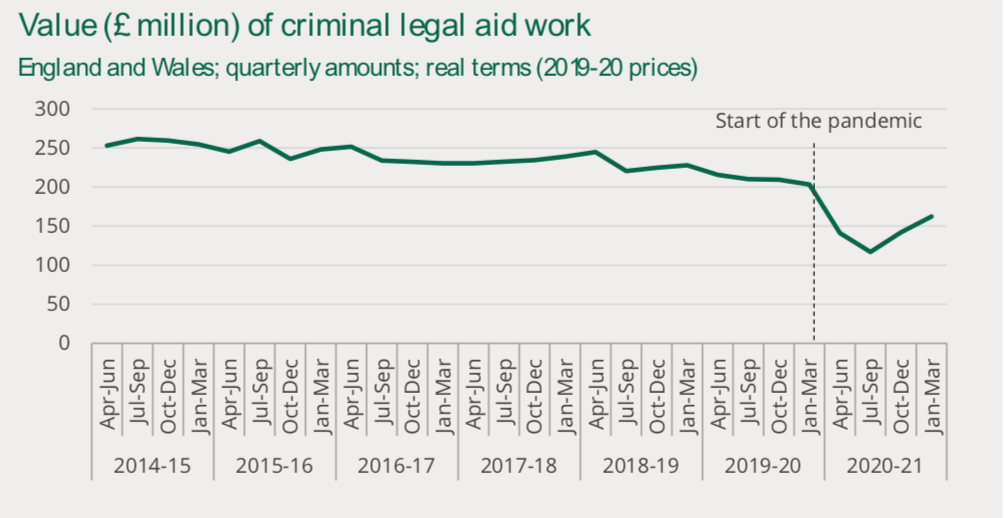

In April-June 2020, spending was down 35% on the same quarter in the previous year; in July-September, 44%; in October-December, 32%; and in the first quarter of 2021, it was down 20% on the previous year. According to data provided by the government’s Independent Review of Criminal Legal Aid since 2014/15 the number of criminal legal aid firms in England and Wales has decreased by 19% (from 1,510 in 2014/15 to 1,220 in 2019/20) and the number of solicitors working in the sector declined by 20% while the number of practising solicitors grew by 9%.

In April-June 2020, spending was down 35% on the same quarter in the previous year; in July-September, 44%; in October-December, 32%; and in the first quarter of 2021, it was down 20% on the previous year. According to data provided by the government’s Independent Review of Criminal Legal Aid since 2014/15 the number of criminal legal aid firms in England and Wales has decreased by 19% (from 1,510 in 2014/15 to 1,220 in 2019/20) and the number of solicitors working in the sector declined by 20% while the number of practising solicitors grew by 9%.

‘Duty schemes are collapsing,’ Richard Miller, head of the Justice Team at the Law Society, told MPs . ‘One in the north-west collapsed and had to be combined with a neighbouring scheme, and others are down to their last three or four lawyers. […] We had 1,122 firms holding a criminal legal aid contract as of 14 December. That is 150 fewer firms than in 2019, so 12% of the supply base has gone in the course of a year.’

According to the Justice Committee, the 20 year pay freeze ‘needs to be addressed’ and a 2014 cut of 8.75% led to ‘a significant contraction’ of the supplier base. ‘I don’t like talking just about money, but the fact is if any of you MPs went out to a builder and said “I’ve got an extension that I need to be built,” and they came back and said, “right, it’s going to cost you £50,000” and you said, “well that’s fine, but I’m only going to pay you what it would cost for me to build it in 1997”,’ Robbie Ross, a solicitor advocate, told MPs. ‘Now how many builders would then take on the contract!?’

MPs concluded that there were ‘serious problems’ with the current fee schemes for criminal legal aid and that fees and rates did ‘not reflect the work required’. They also called for a review of the 2013 means test set at a £37,500 threshold of disposable income above which there is no legal aid. James Mulholland QC, chair of the Criminal Bar Association, called it ‘appalling’. ‘It is a complete contradiction in access to justice. It is called denial of justice in reality. We should get rid of the means test.’ ‘If the means tests for the magistrates’ court and the Crown Court are to remain then the current eligibility thresholds should be addressed and thereafter automatically uprated every year in line with inflation,’ the committee said.

The review highlighted the unfairness of the so called ‘innocence tax’ imposed on those who fail the financial eligibility test and then are acquitted in the Crown Court but can only recoup fees at legal aid rates. The justice committee recommended the government make the system fairer by ‘levelling up and removing the cap on what reasonable costs acquitted defendants may recover from central funds’.