A government minister appeared to reject key recommendations of a two-year inquiry into the miscarriage of justice watchdog in yesterday’s debate about strengthening the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC). The All Party-Parliamentary Group on Miscarriages of Justice commissioned an inquiry into the CCRC after the number of cases of people claiming to be wrongly convicted sent to the Court of Appeal crashed. The so-called Westminster Commission last month called on the CCRC to ‘demonstrate its independence’ from Government and on the government to properly fund the group and to consider a new statutory test to replace the ‘problematic’ real possibility test for referrals.

Alex Chalk, parliamentary undersecretary of state for justice, downplayed concerns about falling referrals, saying: ‘I agree with the CCRC that the referral rate cannot be the only measure of its success.’ ‘There will always be factors outside the CCRC’s control that affect the number of applications and, indeed, referrals it makes in a given year,’ the MP added.

The CCRC has repeatedly resisted criticism for the drop-off in the number of cases sent back to the Appeal judges – for example, its chair Helen Pitcher has insisted that referrals were not ‘the be-all and end-all’.

Chalk noted that in the past 12 months the CCRC had referred 70 cases to the appeal courts. ‘That is more cases than in any previous year,’ he added; before acknowledging that this included multiple linked referrals including 51 cases cases relating to the Post Office Horizon cases. The number also includes six Shrewsbury 24 cases (a case that was initially rejected by the CCRC).

Launching the debate, Barry Sheerman MP, chair of the APPG, said that the CCRC’s budget had been ‘slashed’ and ‘urgently’ needed more resources to ‘fulfil its role’. ‘The figures are not extraordinary,’ he said. ‘They are very modest with respect to what is needed to put things right.’

The Westminster Commission reported that the CCRC had suffered the ‘biggest cut’ of any part of the criminal justice system since 2010. As well as calling for more funding, it said the CCRC ‘needs to demonstrate its independence from government’.

Alex Chalk dismissed concerns over a High Court ruling in 2020 in the Gary Warner case (here) in which a convicted armed robber, whose application to the CCRC had been rejected, argued that the group was not sufficiently free from government control to be independent.

Judges Fulford and Whipple rejected his case but noted at least for a two-year period (2016 to 2018) that the relationship between the CCRC and the MoJ had been ‘very poor during this period, even dysfunctional’.

Chalk said: ’I welcome the High Court’s finding in July 2020 that the CCRC is both operationally and constitutionally independent of the MOJ,’ Chalk said. ‘The judgment found that changes made as a result of the [Ministry of Justice] tailored review undertaken by the Department did not represent a diminution of the CCRC’s independence or integrity.’

That is an interpretation of the Warner judgment not shared by former CCRC commissioners who spoke out about about the likely impact during the review nor by the Westminster Commission and a number of commentators including Dr Hannah Quirk.

Three former commissioners told the inquiry about their concerns. ‘I cannot see how one-day a week commissioners could ever fulfil the duties for which they were appointed… they would find it almost impossible to be anything other than “rubber-stamping” decisions,’ said one. It takes the agreement of three commissioners to send a case back to the Appeal judges.

At the start of the Westminster Commission report, it notes that that CCRC is now ‘operating in a completely different way’ to that envisaged when set up almost 25 years ago. The MoJ review led to a fundamental change at the CCRC. Until 2012 those commissioners were on salaries with holiday, sick pay and a pension; however in 2017 commissioners were recruited on minimum one-day-a-week contracts with none of the benefits. The Westminster Commission heard concerns by the law reform group JUSTICE that the CCRC’s independence had been undermined by the government ‘unlawful interference’.

Barry Sheerman said that the APPG had been ‘rather shocked’ to discover commissioners’ remuneration had ‘declined quite steadily’ and that they were paid on ‘a per diem basis as consultants’. ‘We believe that the move away from more full-time people towards having part-time people working on a per diem basis has not been very good for the organisation’s overall effectiveness.’

Chalk defended the daily rate saying it allowed the CCRC to ‘potentially recruit counsel to work as commissioners where they might not necessarily want to be full-time employees’. ‘It allows the CCRC to recruit high-calibre people to act as commissioners, and it seems to me that that is something to consider properly,’ he added.

Alex Chalk also appeared to take issue with the Westminster Commission’s finding that the CCRC was under-resourced. ‘The MOJ has provided the CCRC with substantial capital funding over the past two years so that it can upgrade its IT systems and improve its casework processes,’ he said. ‘That investment alone totals more than £1.5 million, and it will support the CCRC in delivering high-quality casework.’

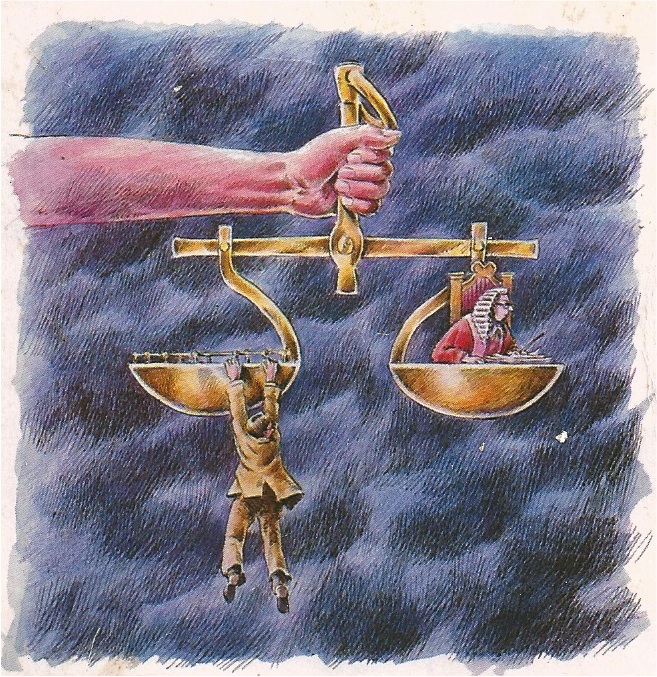

Barry Sheerman called for the government to consider a new statutory test to enable the CCRC to refer more cases. Under ’the real possibility test’, the CCRC must be satisfied that there is such a possibility that that Court of Appeal will overturn a conviction. The ‘predictive nature’ of the real possibility test ‘encourages the CCRC to be too deferential to the Court of Appeal’, he said. ‘It seems to act as a brake on the CCRC’s freedom of decision and we believe that needs reform.’

Alex Chalk doubted the value of revisiting the statute. He argued that a lower threshold (‘mere possibility’) would be likely to be ‘too low a bar’, and continued: ‘Equally, “real possibility” is a far lower bar than exists, for example, when the CPS has to make a decision about whether to charge someone,’ he said. ‘… I accept that this is an inexact science, but it is not immediately clear to me how amending the test would make a material difference. As I say, we will keep the matter under review.’