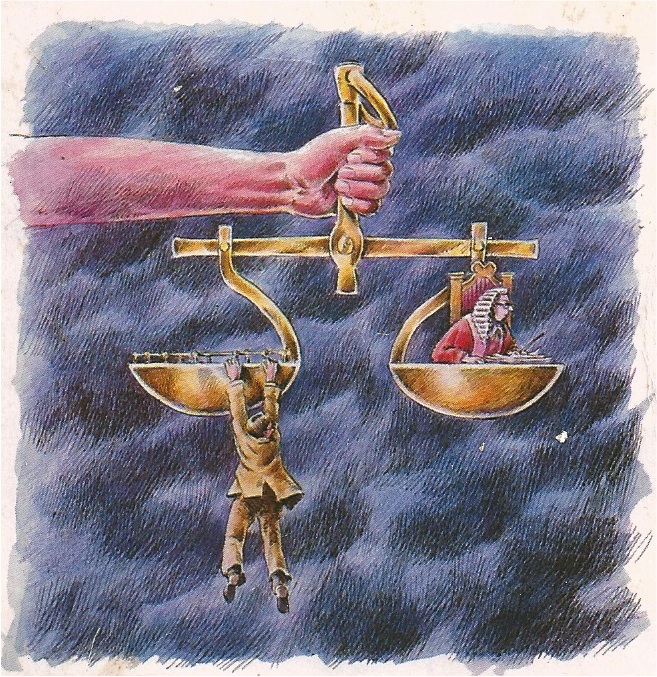

New bail reforms were failing the victims of domestic abuse and harassment, according to a legal charity. The Centre for Women’s Justice argues that a new regime introduced in April 2017 represents ‘an alarming failure to meet the basic police duty to safeguard a highly vulnerable section of the population’.

Since April 2017 police forces have faced a 28 day maximum on bail which can only be extended in exceptional circumstances and anyone the police intends to investigate beyond this period can be released, without conditions, in line with a new ‘under investigation’ status.

As reported on the Justice Gap yesterday, the bail regime was changed under the Policing and Crime Act 2017 to stop suspects being held in legal limbo under a cloud of suspicion for months on end. According to data obtained by criminal defence form Hickman & Rose under the freedom of information legislation people are now being kept ‘under investigation’ for an average of 49 days longer than they were under the old bail regime.

The Centre for Women’s Justice yesterday submitted a super-complaint to the HM Inspectorate of Constabulary including submissions from 11 frontline groups. The group argues that following the change ‘most rape suspects’ were now being released without bail conditions ‘which means no protections for complainants’. ‘Frequently when women subject to domestic abuse report breaches of non-molestation orders police treat them as a trivial matter despite a breach being a serious criminal offence in its own right,’ it argues.

The CWJ submission includes submissions from 11 frontline groups and a number of case studies including ‘Angela’ who was repeatedly contacted by her ex-partner immediately after bail was lifted. Her ex was still ‘under investigation’ for assaults and attempted rape. ‘I have been petrified of leaving my home and unable to continue leading my everyday life as I am scared that my ex will try to contact me again,’ she said.

The group also also points out that the new domestic violence protection notices and orders introduced in 2014 as an additional protection for women were ‘rarely used’ and the police and prosecution frequently overlooked making an application for a restraining order at the end of a criminal case.

‘The system is currently failing women,’ commented Nogah Ofer, the group’s solicitor. ‘ We call on the police Inspectorate, and the other police oversight bodies, to put protection of women at the top of their agenda and take robust action to ensure that all the various legal powers that exist are actually used in practice. Police units dealing with domestic abuse and sexual offences are chronically under-resourced, and police guidance, training and supervision all need to be improved.’

The CWJ reckons this is the second super complaint to be submitted since a new system introduced in November 2018 which allows certain groups to raise issues on behalf of the public about harmful patterns or trends in policing.