Losing its appeal? 20 years of the CCRC

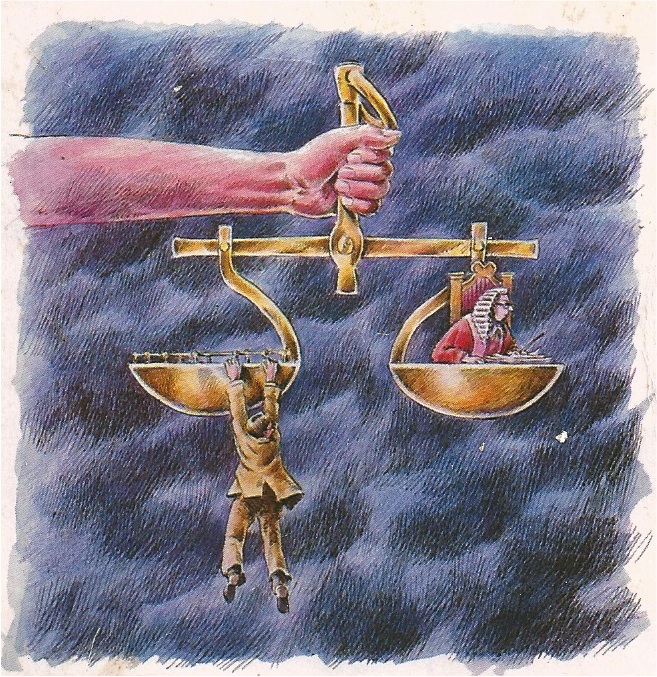

Image from ‘More Rough Justice’ by Peter Hill, Martin Young and Tom Sargant, 1985

It is 20 years since the Criminal Cases Review Commission began its work investigating wrongful convictions. Paddy Hill was one of the Birmingham Six whose convictions for the murder of 21 people in the 1974 pub bombings were overturned in 1991. The day that the six men walked out of the Old Bailey, the Government announced a royal commission that ultimately led to the creation of the first state-funded miscarriage of justice watchdog.

Hill recalls being interviewed by the Home Office before the commission opened. ‘I was asked how many people I thought were innocent in prison. I said about 250. On April 3, 1997 they opened the doors – the Home Office deposited 243 cases with the Commission that morning.’

The Justice Gap is running a series of articles written by students from Cardiff Law School’s innocence project. Over the last 12 years, their innocence project has looked closely at 40 cases concerning people maintaining their innocence and involved some 750 students in their work. See here.

You can read Paul Mayon 20 years of the CCRC here

At the CCRC’s inaugural press conference, its chair Sir Frederick Crawford told journalists that he anticipated an ‘avalanche’ of cases on top of the Home Office files. ‘I don’t know if we can cope,’ he admitted. Funding for the new body was ‘several hundred thousand pounds’ short of what was needed, he added.

Sir Fredrick was a scientist with a fascinating CV (including time at the French Atomic Energy Commission as well as working on the Space Shuttle); but journalists were more interested that the watchdog’s first chair was a prominent freemason.

Over the last two decades there has been much criticism of the CCRC, some fair, some not; recurring themes include inadequate funding, overwhelming caseload and a lack of independence.

The journalist and former commissioner David Jessel, who presented Rough Justice, has called the CCRC’s formation the ‘nationalisation of zeal, the taking of fervour into public ownership’.

Frankly, it was never going to satisfy the expectations of campaigners. ‘I don’t recall much starry-eyed optimism among campaigners when the CCRC was created,’ reckons Paul May who worked on the campaign to free the Birmingham Six. ‘It was very good for the first 12 to 18 months,’ reckons Paddy Hill. ‘But then the gates came down – and then they locked the gates.’

Michael Zander QC, emeritus professor at LSE, was on the original Royal Commission. ‘There was a unanimous view that the business of miscarriages of justice had to be taken away from the Home Office,’ he says. ‘No one quarrelled with that at all.’ He recalls the Home Office’s shadowy C3 department as ‘a pathetic little organisation’.

Crumbs off the table

Two years ago the House of Commons’ justice committee gave the CCRC a lukewarm review saying that it was performing its job ‘reasonably well’. The chair Richard Foster told MPs that over the last decade the commission had its budget slashed by a third as its workload increased by 70%. ‘For every £10 my predecessor had a decade ago, I have £4,’ Foster said.

The miscarriage of watchdog has been consistently undermined by successive governments. The former CCRC commissioner Laurie Elks wrote a 10 year review of the watchdog published by JUSTICE in which he noted that the CCRC ‘generously funded in its early years’ had quickly become ‘regulated from a spirit of underlying hostility’.

Professor Graham Zellick in 2007 revealed the extent of the unhappiness at the then relatively young organization. At that point in time, the watchdog was facing cuts of £300,000 a year for the next three years. Zellick reported, in the CCRC’s annual report, his staff were ‘frustrated … angry and dispirited’. I interviewed the academic around this time. ‘If you compare our £8 million budget with the amount of money spent on the other side by the police and the Crown Prosecution Service, it isn’t even a crumb off the table,’ he told me.

How would the CCRC describe its contribution to the justice system? ‘First, there are the 630 individuals whose cases we have re-investigated and referred back to the courts – two or three a month for the last two decades,’ Richard Foster begins. ‘These are convictions of the most serious sort, murder, rape and the like.’ According to Foster they include some of the ‘most significant and high profile cases of recent decades’ such as Sally Clark, Barry George, Sean Hodgson, Sam Hallam and Alexander Blackman.

Secondly, he points to the role of the CCRC as ‘part of our constitutional checks and balances’. ‘No part of the criminal justice system is above the law,’ Foster continues. ‘Prosecutors, defence lawyers, the police and even high court judges get it wrong from time to time. When they do, the resulting injustice needs to be put right.’

Finally, Foster argues that a review that does not deliver a referral back to the courts as a potential miscarriage is ‘not a failed review’. ‘It is a review that confirms the conviction is securely based thereby helping maintain confidence in the system,’ he says. ‘Only a very small percentage of the cases we look at are – in our judgement – potential miscarriages. And in our view that is as it should be in a well functioning system.’

Partly excellent, partly abysmal

Paul May has been involved in numerous campaigns from the Birmingham Six, Judith Ward, and the Bridgewater Four through to Sam Hallam, whose murder conviction was overturned in 2012, and Eddie Gilfoyle who has been trying to clear his name for the murder of his pregnant wife in 1992.

‘Like the curate’s egg, the CCRC’s record is partly excellent and partly abysmal,’ May says. Their investigation into the safety of Hallam’s conviction was ‘exemplary… leaving no stone uncovered’. But May says: ‘The CCRC’s irrational dismissal, after more than five years’ investigation, of overwhelming evidence supporting Eddie Gilfoyle’s innocence was beyond absurd.’

The CCRC and the 2015 justice committee gave considerable weight to the research of Dr Stephen Heaton. He found nine out of 10 applications to the CCRC had no prospects of even being looked at by the body. Of the total number of applications, some 3.5% were referred to the Court of Appeal. The academic focused on 147 such cases where the CCRC did not refer and identified 26 where there was concern of a potential miscarriage of justice. Of that number, Dr Heaton came to the conclusion that the CCRC was right not to refer them based on the current statutory test. ‘That’s a very important finding in a really serious piece of research,’ Zander told the MPs.

‘The study is six years old. The world moves on,’ says Dr Heaton. The academic raises a number of concerns not captured by his research: the now 3% referral rate could be as low as 1% (if you disregard asylum cases); increasingly thin statements of reason for those cases it rejects; and a run of adverse judgments in the Court of Appeal.

The CCRC insists that ‘there is no shortage of tenacity’. The fact that the statements of reasons are often shorter – ‘we would say, more concise,’ it adds – ‘should not be take as a sign that there is’. The commission reckons that the statements were ‘often simply too long and too legalistic – particularly when you consider that most were sent to people who were not represented by a lawyer and in order to explain why we are not referring their case’.

Another common complaint from practitioners is the CCRC’s attitude to legal challenges. There were 28 judicial reviews of its decisions last year in 2015. Whilst the watchdog has only lost one JR in its 19 years, it often concedes and last year two were conceded before application and one after a hearing.

Lawyers argue that is hardly the conduct of a proactive watchdog. The CCRC says that if they think a JR has raised a point with ‘sufficient merit that it can only be addressed by revisiting the decision, we will simply concede at the earliest opportunity and take the appropriate action rather than enter expensive litigation regardless of whether or not we think we would prevail in Court’.

Baptismal curse

Whilst the CCRC was created independent of government, it was never free of the courts. Only cases with a ‘real possibility’ of being overturned can be referred to the Court of Appeal. David Jessel calls the statutory test ‘a baptismal curse’. Paddy Hill reckons the CCRC is a ‘bastardisation’ of the original proposals. The government ‘only did half the job’ and should have built a system separate of the courts, he argues.

Tom Sargant, the first secretary of JUSTICE, argued for a determinative body that would consider alleged miscarriages of justice independently of the courts. Chris Mullin MP, then a campaigning journalist, called for a court of last resort comprising ‘a clear majority of non-lawyers’ with ‘the power to quash that conviction without further reference to the Court of Appeal’.

The debate around miscarriages has shifted markedly from the inadequacies of the CCRC (perceived or otherwise) to that of the Court of Appeal. In Laurie Elks’s 2008 study of the CCRC, he noted that the court had already ‘wearied’ of the Commission’s referrals and had ‘not hesitated to administer a prefectorial ticking off when it considers that the commissioners overreached’.

The most significant recommendation made by the 2015 House of Commons’ justice committee was for the Law Commission to review the Court of Appeal’s grounds for allowing appeals. However it was rejected by Michael Gove seemingly on the assurance of a belated written submission former Lord Chief Justice, Lord Justice Judge – although as reported by the Justice Gap last month the Law Commission shortlisted the issue as a possible area of inquiry.

Michael Zander had told the MPs that the Court of Appeal has always failed to get to grips with some miscarriage cases. ‘The Court of Appeal is the crucial issue,’ the academic says. ‘It is hopeless, completely hopeless. They won’t budge from their position which they have taken and held for more than 100 years’.