The veteran investigative Bob Woffinden argues that the media has given up on serious public interest coverage of justice issues. The press benches are empty. This article features in the latest issue of Proof magazine (here).

As the trial of Jonathan King, the music industry personality, was about to begin in September 2001, the judge imposed a blanket ban on media coverage of proceedings.

The trial would concern allegations of sexual assault against teenagers. The judge, His Honour Judge Paget QC, had resolved that certain of the allegations should be heard separately at a second trial. He reasoned that he did not wish media coverage of the first trial to contaminate the second.

UK news organisations were deeply indignant. How dare the judge presume to constrain the historic right of the media to report criminal proceedings in open court? This was a fundamental infringement of the privileges of the fourth estate.

The major broadcasters and publishers – the BBC, et al – joined together in a collective action and instructed leading lawyers to argue that they should be allowed to report proceedings. The start of the trial itself was then delayed while this media challenge was heard.

The upshot was that the media lost. The trial went forward as the judge had intended it to, in the absence of media reports.

The trial then ran its course. King was found guilty and sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment. So now, finally, the media had the opportunity to report everything that they had hitherto been prevented from publishing.

REVIEW: You can read David Rose’s review of Bob Woffinden’s latest book The Nicholas Cases here – and buy it at www.bobwoffinden.com

REVIEW: You can read David Rose’s review of Bob Woffinden’s latest book The Nicholas Cases here – and buy it at www.bobwoffinden.com

‘If only the complacency [that British justice is the best in the world] was well-founded. As Bob Woffinden shows in this new, essential book, nothing could be further from the truth, and if anything, in the wake of swingeing legal aid cuts, the situation is getting worse, not better.’

David Rose

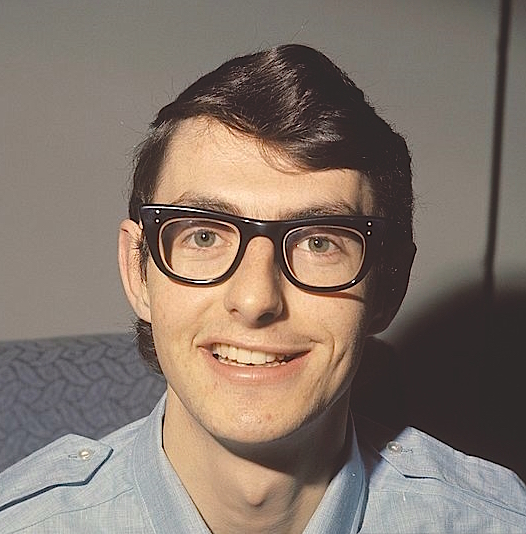

Fair trial? A 20 year old Jonathan King

Dirty tricks

As it happened, two intriguing developments occurred during the trial. King essentially proved his innocence of many of the specific charges against him. Remarkably, the judge then allowed the indictment to be changed. This left King facing different charges, albeit ones to which he had not been allowed to present evidence in his defence; the indictment was only changed after the evidence had been heard. This appeared a breach of the UK’s commitment to fairness in criminal proceedings.

In fact, it also demonstrated how finely-balanced the trial was; if the Crown had needed to resort to such tactics, then a conviction can hardly have been in the bag. One repercussion of this changing of the indictment was that, over the following years, King was able to prove that he was in the US at the exact time that he had been, according to the prosecution, committing an offence in the UK.

The second point was that the judge, having heard all the evidence, aborted the second trial and directed that King be found not guilty of all further charges.

King’s being such a high-profile case, one would have imagined that the media would be impatient to report it all, paying particular attention not only to the verdict but also to these exceptional features.

At the pre-trial hearing, lawyers for the media would have argued the right of the media to publish ‘full, fair and impartial’ reports of proceedings; but what happened here demonstrated that the UK media simply had no interest in publishing fair and impartial accounts of court proceedings.

On his conviction, King was portrayed in lurid and sensationalist terms as a sexual predator who well deserved a long prison sentence. The news organisations were interested only in the journalism of nastiness, in which a target has his reputation traduced and is portrayed in the most malicious terms.

No news outlet mentioned that he was acquitted of many charges, or that much of the evidence failed evidential tests, so putting the Crown in the embarrassing position of having to change its own indictment.

At least – let me revise that – it would have been embarrassing had the papers done their job and reported it; they didn’t, so it wasn’t embarrassing at all. The Crown could employ dirty tricks with impunity.

It should be emphasised that in one sense the media cannot be blamed for failing to report accurately what had been going on. In fact, they had no idea what had happened because they weren’t there.

It is a convenient fiction that newspapers cover trials. They do not. For the majority of the time, even if the case is a major one, the press benches are empty. Perhaps an agency reporter, hoping to sell a story, will drop by from time to time. Of course, there are very rare exceptions – of which the Ched Evans case is one – but, in general, that’s the position today.

Two factors about the King trial should be borne in mind: firstly, this was the case of a very prominent personality; and secondly it all happened 15 years ago. Matters have deteriorated significantly in the years since.

I was speaking recently to a juror who’d served in a trial in which the defendant was found guilty and sentenced to sixteen years’ imprisonment. She told me the trial had received no media coverage at all. Maybe not nationally, I replied, but not even locally? Not even in the local media, she confirmed. Yet sixteen years is a considerable and, one would have imagined, newsworthy term of imprisonment.

Bob Woffinden’s 1987 book Miscarriages of Justice

published in 1987

A sea change

It used to be so different. In the 1950s, proceedings in the major criminal trials of the day – for example, of Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be hanged, or John Straffen, the notorious child-murderer – would be fully covered. Frequently, the evidence would be reported verbatim. If cases didn’t reach that level of national prominence, then there would be full pages of reports in local newspapers. Indeed, if a criminal case took place in the century between, say, 1860 and 1960, then you can usually guarantee that you will find detailed contemporaneous reports in publications in the British newspaper library.

Since then, there has been a sea change. There is a cluster of reasons for this, the first of which is the length of trials. The Ellis and Straffen trials provided concentrated drama for the press to seize upon; they were over inside three days. By 1962, the trial of James Hanratty set a new record for the longest murder trial in UK history; it lasted almost four weeks.

Subsequently, trials just became more and more protracted. Today, despite courtroom management and various attempts to rein in their length, they may still last several weeks. The concentrated drama was lost; newspapers’ interest began to dissipate.

The trial of Rebecca Brooks and others on phone-hacking charges was, in some quarters, dubbed ‘the trial of the century’. Even though the prosecution and the personalities involved fell foursquare within the media’s principal areas of interest, the progress of the trial, which resulted in Brooks’ acquittal, was only intermittently acknowledged. It lasted from 28 October 2013 until 24 June 2014 and was conscientiously covered only by Private Eye.

Thirdly, the nature of crime changed. The unceasing flood of inventive crime dramas for television and the cinema might lead one to suppose that crime stories are exciting per se but, of course, they are not. The crime that was actually taking place became devoid of interest; the brutal became mundane, the criminality more mindless and whatever public fascination there had once been now evaporated.

The flurry of excitement surrounding the Hatton Garden safe deposit robbery in April 2015 perfectly illustrated this. The media’s interest stemmed precisely from the fact that the robbery seemed a throwback to the heady days of UK crime of half a century earlier. There did seem to be something deeply fishy about it all. A CCTV recording of the incident was released by the Daily Mirror, not the police. It was as if the men, who were all pensioners, had been set up just to provide some nostalgic entertainment.

Increasing numbers of Asian men were taken to court accused of serious crime and, unless there are exceptional circumstances, the media simply isn’t interested in Muslim defendants. Also, the number of sexual assault cases mushroomed. As a rule, the complainant could not be identified and this frequently meant that the accused, if he was a family member, could not be identified either – so neither were those cases reported.

There were also mounting financial pressures, especially with the arrival of the internet. Papers simply couldn’t afford to have reporters tied up for weeks at a slow-moving trial when other domestic stories needed to be covered.

The upshot of longer trials, uninteresting crime, depleted budgets and reporting restrictions is that trials, in so far as they are reported at all, are reported in an entirely partial way. Reporters generally just turn up for the prosecution opening at the start and the verdict at the end. They have no idea what’s been going on in between. So they rely for their information on the police, who do have the resources to prime the media. Accordingly, if criminal trials are reported in any way, they are reported from the standpoint of the police and prosecution.

Media bias

Some may point out that it was ever thus, and they would have a point. The key factor, though, is that in the days when court evidence was being extensively published, at least the public would be able to gauge the strength of the prosecution and defence arguments for themselves. Today, not only is the evidence unreported in major cases but a high proportion of trials, some with extraordinary features, may never be reported at all.

Of course, all this has knock-on effects. Firstly, reporters can have no confidence in what are purportedly their own reports. This leads to the dissemination of a single viewpoint and there are no counterbalancing opinions.

One of the guarantees that we are all being properly informed is the plurality of the media; there are, so the theory goes, many news organisations in the country and therefore many differing viewpoints will be expressed. But this is no longer the case with criminal justice. Only one viewpoint is now represented; the voice of the defence is not heard at all.

In the 1950s, a very famous episode occurred in relation to the trial of Bodkin Adams, a doctor in general practice who was accused of murdering elderly patients. Percy Hoskins, the well-respected Daily Express crime reporter, stood apart from his Fleet Street colleagues in steadfastly believing in Adams’ innocence.

Adams was indeed found not guilty and Hoskins later wrote his account, entitled Two Men Were Acquitted: i.e. Adams and himself. He explained how difficult it had been for him to have reached an analysis of the case that contradicted the collective view of his colleagues. The board at Express newspapers were concerned that his stance might cause the paper to suffer losses of advertising and circulation; but, ultimately, the paper allowed him to write what he believed.

Admittedly, that famous episode does demonstrate how rare it has been for leading journalists to hold dissenting views in this field. The point is, however, that there is no possibility today of sharply divided views of a major criminal case being reflected within the media.

Knowing that the prosecution, police and press are essentially acting in concert, defence lawyers have inevitably concluded that the media cannot be trusted. The legal teams warn their clients against any media involvement and offer no briefings themselves to the media. Obviously, this just reinforces the whole process: media bias inevitably leads to more media bias.

But it is the internet itself that has had a deeply deleterious effect on public interest reporting. The press simply hasn’t been able to withstand the online competition. As social media have forged ahead and imposed a news agenda of their own, so the press has capitulated to their values. Apart from anything else, it’s much cheaper to pick up and recycle stories that are already in circulation rather than to pursue original material. But there is also a long-established convention in the media that no one wants to be seen to be missing out on a story that its competitors are reporting – and competitors certainly include online media. And so the news agenda has been transformed.

Clickbait

Public interest news values were traditionally defined as matters that – in the public interest – ought to be generally known; now, after the entrenchment of social media, the public interest has been redefined as news that members of the public, even if momentarily, are actually interested in.

Moreover, we know what they’re interested in, because we can tell that from the number of clicks that a story receives. This is now the criterion that dominates all others. Virtually all media publications feature ‘Top 10’ lists of their most-read stories. So a story about, say, a man grappling single-handed with a crocodile will displace a news report about some development in the criminal courts; it will attract clicks in the tens of millions whereas the latter will receive negligible attention. Public interest news values, as we once understood them, are no more.

According to these new news values, whether a story is actually important is, of course immaterial; further, whether or not it is actually true is also irrelevant. After all, it is as easy to disseminate an untruthful story as a truthful one; and the former is likely to be more scandalous and thrilling and therefore more clicked-on. The upshot has been that ‘post-truth’ was declared to be the word of the year for 2016.

While this has implications for all news reporting, it is the repercussions in the context of criminal justice that especially matter. Social media discussion tends to be not only not rational but not even discussion at all. It tends to be frequently abusive and dominated by the intolerant. What is fascinating is how this rancorous and vituperative character of social media chimes precisely with the journalism of nastiness that has in recent decades been practised by the UK national press – especially the tabloids. Really, there was an inevitability that the one would reinforce the other.

Those whose voices are the loudest in what is supposed to be public debate about criminal matters are those who have no time for the careful deliberations of the criminal justice process; they are those who are impatient just to get whoever is perceived as the malefactor convicted, jailed and utterly ruined at the earliest opportunity. The more considered voices of those championing defendants are never heard.

However damaging in individual cases, this is hugely detrimental for the warp-and-weft of public debate about the efficacy of the system itself. It means that there is no public avenue through which defence concerns may be ventilated. As a result, MPs and, indeed, the authorities and administrators generally are uninformed; all they can hear are the voices of the baying prosecution pack. MPs voted to put police officers on juries in the UK. But have any of them ever thought about what this has meant in practice?

Parliament often reacts to alarmism in the popular press, and all this pressure is now one-way. It is certainly no coincidence that virtually all changes to the criminal justice process made this century – i.e. in the wake of the arrival of the internet – have brought additional succour to the prosecution. The thrust of legislation has been to make it easier to convict more people of more offences.

One of the contradictions of all this is that, even understanding all the drawbacks, one would still advise any campaign against injustice to obtain publicity if it possibly can.

There can, though, be no rose-tinted perspective. The Times’ championing of Eddie Gilfoyle’s case for the past eight years or so has been admirable indeed, but all it has so far demonstrated is the impotence of even The Times in this area. It is also evident that its campaign has been an isolated one; no other national media organisation offered support. This is in sharp contrast, for example, to the campaigns for the Birmingham 6 and the Guildford 4 in the late 1980s which were supported by a range of media organisations.

It is also true that the new online media does have the capacity and the influence to organise matters differently – as Netflix showed with its Making a Murderer series, which one hopes will one day prove to have been seminal.

Until that happens, there is the current reality: the reassurance that we have a free and unfettered media to report criminal trials, and that we have a plurality of media organisations to offer comment on aspects of the system, are empty reassurances.

In the realm of criminal justice, the media betrays us all on a daily basis.